Thomas Woodruff

“RESURRECTION”

New York, 43 Clarkson Street

When the lockdown began, I started drawing dinosaurs. Isolated in my Hudson Valley barn studio, in between countless zoom meetings and online college art classes, I completed over 50 small compositions in several months. “Why on Earth?” my friends would ask.

I was not entirely certain– it was compulsive behavior. It could be because I could project emotions onto them. Obviously, they are all amazing and beautiful shapes, and if we consider their fates, dinosaurs are pathos-plus! They are scaly chalkboard avatars to smudge and erase and calculate upon. They wander somewhere in the crags of our unconscious, hard to completely believe in, as much myth as fact. They allowed me to be fanciful during a trying time.

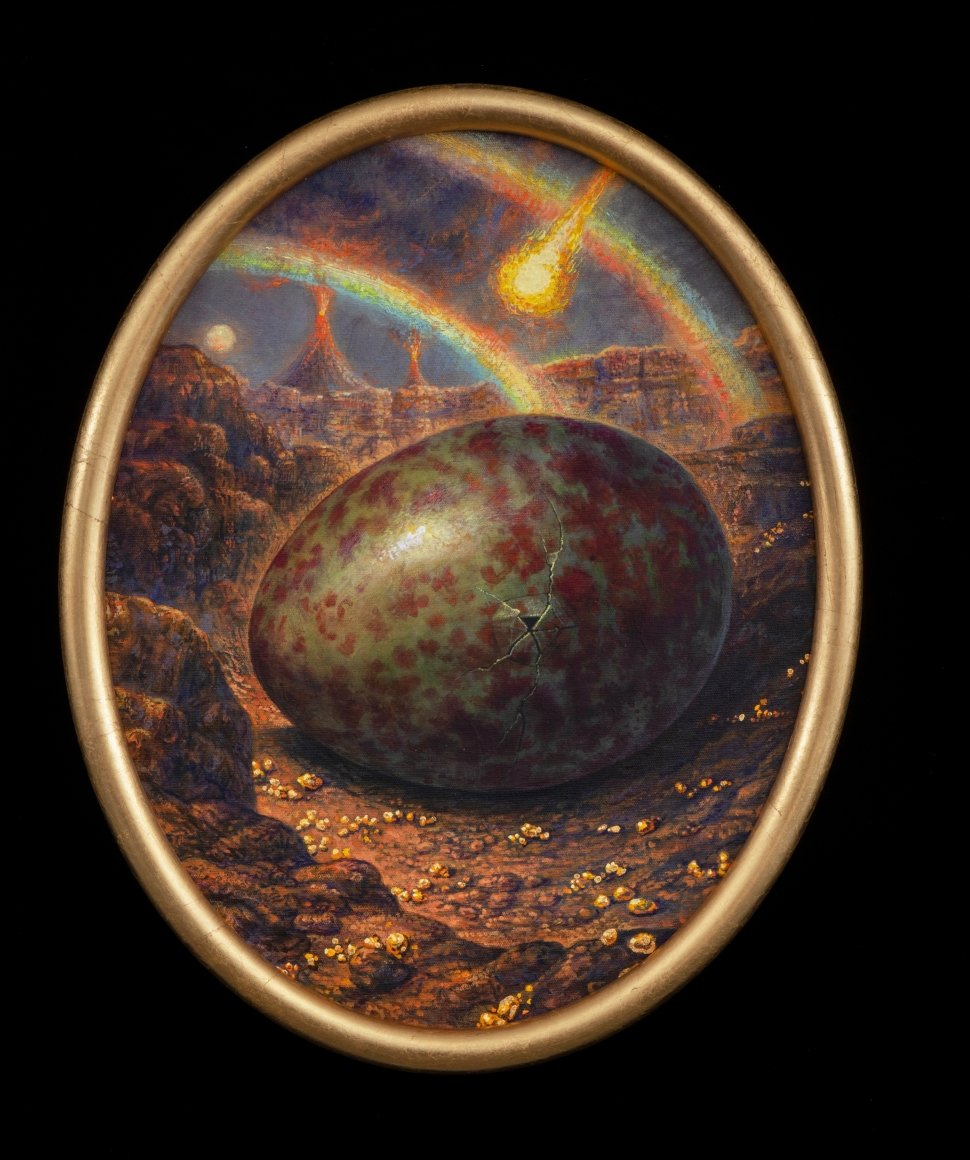

When I began to make large paintings of the beasts and their world, I chose to paint their eggs similar to the size of a human head. Dinosaur eggs imply both grandeur and vulnerability simultaneously. They are iconic objects filled with symbolism and portent, particularly if you show all the odd spots and the poignant cracks of promise.

When I was 11 or 12, I was given a set of pastels and a pad of fancy paper to work with. I drew a series of anthropomorphic vegetables and fruits with big, teary eyes and buck teeth, coy smiles, and cryptic expressions. My family offered them as a special part of a house yard sale, and they sold out! So it was early on when I realized I had the ability to impart some soul to those things seemingly thought of possessing none.

Dinosaurs are almost always depicted as being fierce, could I make them fey? Could they move from their diorama habitat to a grand opera stage? Do they sleep? Cry? Contemplate? Ponder in awe? If so, would they just seem ridiculous? I was completely uninterested in the didactic genre of Natural History painting, specifically “paleoart”, nor was I intrigued by contemporary fantasy movies, where the beasts had but one emotion: RAGE. I am attracted to the quaint dinosaur sculptures made at the turn of the century for the Crystal Palace in London by Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins. Incorrect by modern standards, and displaying all the inaccuracies of early paleontology, the figures have an innocent gravitas. I love the fact that the artist held a New Year’s Eve dinner inside the mold of his Iguanodon in 1853.

I thought I could incorporate an approach from Renaissance and Romantic artists (though they thought more of dragons than dinosaurs), who depicted the pious monk in the wilderness, the lonely man contemplating the cosmos, or the figure witnessing the approaching cataclysm. I was interested to see what would happen if Titian broke bread with Spielberg, if Caspar David Freidrich kissed Ray Harryhausen, if Jean-Antoine Watteau and Charles Knight bumped fists.

My pictorial rules were derived from a traditional “Theme and Variation” musical structure. Each image would include some form of: a dinosaur (in either egg or grown incarnation), a rainbow atmospheric effect, a volcano, a moon, and an asteroid. The dinosaurs’ depictions could be fairly flexible, as almost all representations have been. Extinction gives one extraordinary license to drape flesh on bones…I could reinvent, idealize, embellish, and arrange my cast into carefully posed tableaus.

I have a penchant for delving deeply into imagery that is seemingly rendered impotent, or hackneyed, or forgotten, or in questionable taste. I have taken many deep breaths and tried to resuscitate the corpses of the kitsch with new insights. In my oeuvre, I've nurtured crying clowns, sideshow banners, pirate treasure maps, tattoo flash, rocket ships, upside down heads, “ an apple a day..." adage, and balloon animals (rendering them way before Koons). All those disparate tropes made sense to describe my neo-romantic “feelings" at the given time, metaphorically dealing with illness and loss, and as a conceptual figuration artist, these familiar threads have made a solid silken tapestry for me. I have tried to bring pageantry to the quotidian.

Having worked early in my career as an illustrator, and having taught the subject for decades, I am sensitive to narrative languages. My love of pictures, drawing, and design, makes formal compositional and coloristic strategies crucial. These two different directions drive my creative process. Often the viewer will focus on one aspect of the image more than another (the content vs. the formal), but all one really needs to do is to bring their best eyes. I leave enough clues, I hope, for them to do the rest. Like a good waltz, you hopefully can't resist being swept away.

Turning 65 this year, there are parts of the “Dinosaur Variations” that could be interpreted as autobiographical. I am a relic from more than one epidemic, and (like many) have been battered by quickly changing times. Some of the definitions of resurrection are: coming back into use or importance, the spiritualization of thought, and rising again after a time of inactivity. In this new Spring, I hope my new daubed musings appear poetically appropriate. The series is a paean for adroit adaptation, or perhaps for the melancholy inability to do so.

The major theme in the new works is an exploration of grace in the face of annihilation.

– Thomas Woodruff