Cameron Welch

“RUINS”

New York, 245 Tenth Avenue

Cameron Welch meticulously assembles hand-cut bits of marble, stone, glass, and tile, to produce his monumental mosaics. His intricate compositions recount epic stories of contemporary life in America, laden with references to ancient mythology, art history, and his identity. Mosaic, the artist’s medium of choice, allows each constituent piece to embody its own history while simultaneously contributing to the work’s grander narrative.

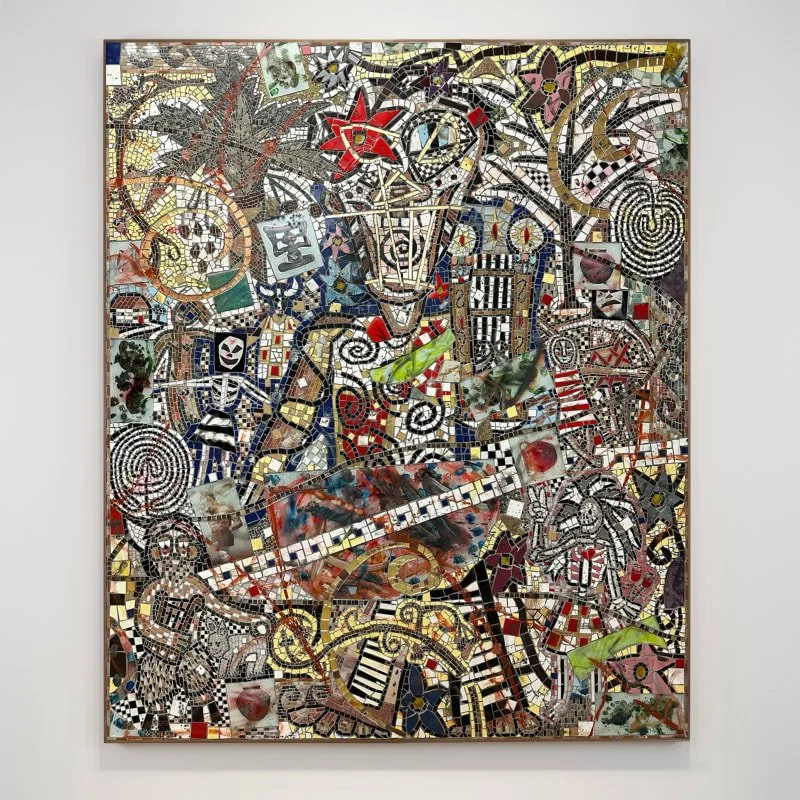

Fugue State, 2021 Marble, Glass, Ceramic, Stone, Spray Enamel, Oil, and Acrylic on Panel

Mosaic has been practiced globally since antiquity, yet its legacy in African art history and culture is often overlooked by western art institutions. Welch seeks to highlight and remedy this oversight with works such as Fugue State (2021). At eight feet high and twelve feet wide, the work is a massive feat in both scale and complexity. In content, it blends iconography from European Christianity, consumer culture, and modern-day socio-political issues, making notable reference to Michelangelo’s Pietà. At its center, a lifeless, Burberry-clad body is draped across the lap of a winged deity. Surrounding these figures is a frenzy of iconographic elements, including a Byzantinesque lamb, masks from the horror film Scream, an anti-cop protester, and a devil-artist dancing atop a Modigliani-like figure of his own creation. Gold-plated glass and marble-printed porcelain tiles are dispersed across the mosaic’s surface, humorously referencing the fabricated surfaces of Welch’s childhood home. This playful mix of codes begets a more serious consideration of displaced peoples and histories, or what the artist refers to as a “black hole of nostalgia.” With a masterful command of his medium, Welch builds worlds that challenge viewers to reconsider who and what ought to be immortalized in marble and stone.

In Plein Air (2021), the artist toys with the notion of self-portraiture, imbuing the work with a liminality that reflects his lived experience as a biracial person in America. The central figure stands behind a literal canvas embedded in the mosaic. He holds a paint palette in one hand and a combination hammer in the other, references to Welch’s training in oil painting and pivot to mosaic. Yet the title, Plein Air, suggests an outward view of an outdoor scene, reiterated by the presence of wildlife creatures and a towering palm tree. The question is begged: is the depicted figure the artist himself or someone he observes? A jagged white line and winding paint strokes disrupt the composition, suggesting both may be true. This nonlinear approach to storytelling grants Welch the freedom to construct spaces wherein dualities coexist. The result is a pictorial space cluttered with an assortment of symbols, masks, animals, and complex tilework. Within this space, chaotic as it may be, the artist has free reign to explore his identity in all its complexity.