Neo Rauch

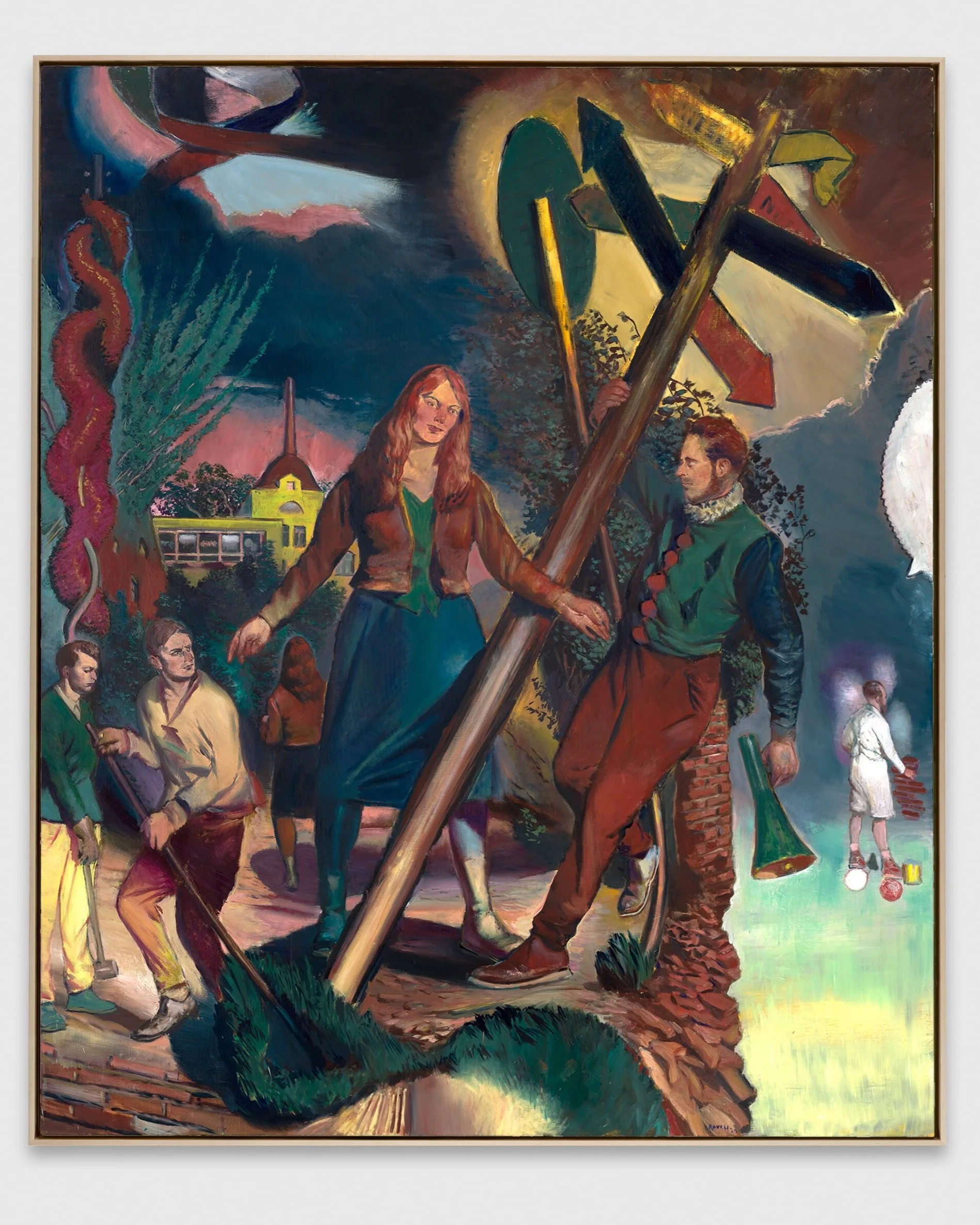

“The Signpost”

New York, 533 West 19th Street

Widely celebrated as one of the most influential figurative painters working today, Rauch is known for richly colored and elaborate paintings that contain a repertoire of invented characters, settings, objects, and motifs. At once realistic and familiar, enigmatic and inscrutable, his paintings often hint at broader narratives and histories—seemingly reconnecting with the artistic traditions of realism—yet they are dreamlike and frequently contain disparate and overlapping spaces and forms. As writer Thomas Meaney notes, “Rauch is known for … huge, dense, ostensibly narrative scenes in which narrative is stubbornly elusive. Events seem to take place in a parallel world. Portions of a canvas can be futuristic, with space-age infrastructure, while elsewhere there may be a sky out of Tiepolo and people who have come from the Napoleonic Wars or some primordial Europe. Rauch’s figures are bound together in tight compositions that recall Renaissance art one minute and socialist realism the next, and yet they remain sealed off from one another, unaware of anything around them, and their actions have a suspended quality.”1 Though his art is highly refined and executed with considerable technical skill, Rauch himself stresses the intuitive, deeply personal nature of how he works. As the artist notes, “My process is far less a reflection than it is drawing from the sediments of my past, which occurs in an almost trance-like state.” 2

Neo Rauch Wegweiser, 2021 Oil on canvas 118 1/8 x 98 3/8 inches (300 x 250 cm) Framed: 120 1/8 x 100 3/8 inches (305 x 255 cm) Signed and dated recto; signed, titled, dated, and inscribed verso

In these new works, Rauch continues to explore figuration and the ambiguous nature of meaning in visual art, while also responding to the his own experiences of the present day. Several of the new works feature prominently positioned signposts, from whence the exhibition gets its title, with arrows and directional markers pointing in myriad directions, seemingly alluding to the disorientation of contemporary life. In the large-scale painting Wegweiser, which translates to “signpost” in English, several individuals cluster around a signpost and appear to be bartering with each other. One figure holds bulbous alien-seeming forms with protruding antennae, which mimic the antennae of several larger forms that appear adjacent to the group. These retro-futurist objects have become motifs in many of the artist’s paintings, an example of how forms, figures, and even certain stylistic flourishes exist as personal iconography that Rauch frequently draws upon and reincorporates into his work. Self-referentiality often mixes with art-historical allusions in his paintings, and in this work, a figure with a rucksack recalls Gustave Courbet’s La Rencontre (Bonjour Monsieur Courbet) (1854; Musée Fabre, Montpellier, France).

Rauch in his studio, Leipzig, 2021. Photo by Uwe Walter

The large diptych Der Zwiespalt—meaning “the discord” or “the dichotomy” in German, is presented as one continuous narrative, with the same or related figures appearing multiple times within the compositions. The two panels offer an allegory of art and the experience of the artist, from the private creative domain depicted in the left panel—in which figures in white cultivate flames within a glowing cave—to the right panel, seemingly representing the public realms, where the artwork and the artist are forced to respond to broader social forces. In the center of the composition is an artist being pulled, against his will, into the second panel by figures in black. Rauch paints several signposts within the right panel, one of which is massive and appears broken and toppled over. Figures in red—assistants or supporters of the artist—are shown hauling directional signs toward an unknown underground space, adding additional conceptual and figurative depth to the painting.