Rene Ricard

“Growing Up in America”

New York, 455 West 19 Street

Rene Ricard was an important voice in the cultural discourse of his era, and his words still carry the authority of his role as witness, critic and observer to a pivotal moment in American culture. His fevered imagination, fierce wit and intellectual acumen, along with his famed bon vivant demeanor and talent for conversation, flow through the stream- of-consciousness prose central to his art. Having moved to New York in the early 1960s at the age of eighteen, Ricard quickly absorbed himself into the transgressive experimental ventures and celebrated debauchery of Andy Warhol’s glittering, silver foiled Factory. By the early 1980s, Ricard had cemented his reputation as a poet and achieved status in the art world, asking the question “What is it that makes something look like art?” in his breakthrough 1981 Artforum essay The Radiant Child, which catapulted Jean-Michel Basquiat’s rise to prominence. This influential text is considered a seminal piece of twentieth century art criticism. Similarly, Ricard’s editorials for Artfoum during the 1980s helped to advance the careers of such artists as Keith Haring, Brice Marden, Julian Schnabel and Francesco Clemente.

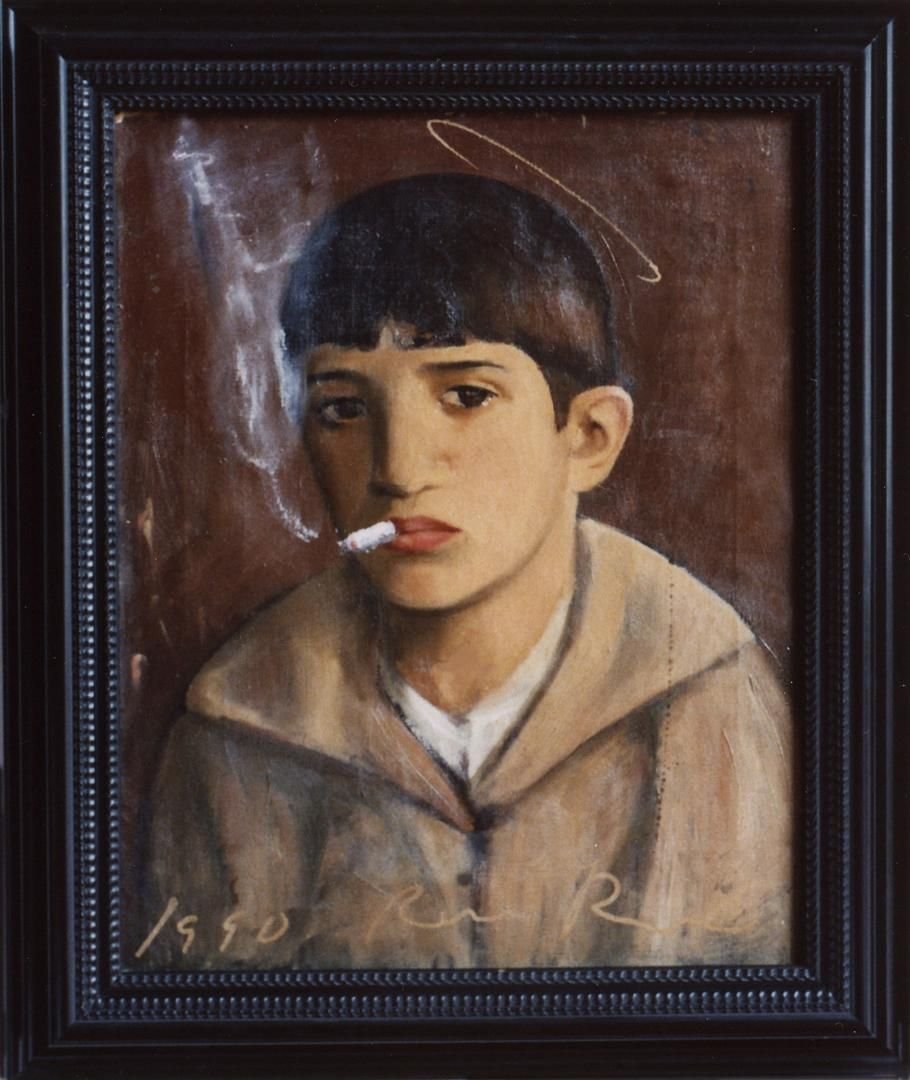

Rene Ricard Boy with Cigarette , 1990 Oil and gold felt-tip marker on linen 20 x 17 inches (51 x 43.2 cm) © Estate of Rene Ricard; Courtesy Vito Schnabel Gallery

Assimilating imagery and text onto almost any surface of his choosing, Ricard began to develop his poems into paintings in the late 1980s. These ‘poem paintings’ employed antique prints and found paintings that Ricard had often thrifted in secondhand stores. In some cases, Ricard would paint over the original surfaces entirely, wiping out the pre-existing images. Ricard also painted his own canvases, depicting figures from old photographs and other sources. Mixing pigments and oils, he created sultry, subdued and seductive colored paintings that were lurid and ghastly, articulated in a gestural palette of smoky black, chalky grey, fiery red, or his lauded acidic ‘poison green.’ Fellow art critic Robert Pincus-Witten attributed Ricard’s ‘poem paintings’ to a strategy rooted in early modernism, connecting him to a lineage that included the calligrams of Guillaume Apollinaire and the picture poems of the Surrealists.

Rene RicardUntitled (What Every Young Sissy...),2007Acrylic, charcoal, Conte crayon, and oil on canvas51 x 33 1/2 inches (129.5 x 85.1 cm)© Estate of Rene Ricard; Courtesy Vito Schnabel Gallery

In a loopy, cursive script, Ricard rendered lines of poetry, stark aphorisms, and terse epigrams that evince his Wildean wit. Against the dark surface of one canvas, a seated classical nude is overpainted with bronze. Below her statuesque body, Ricard has cunningly added his dictum: “what every young sissy should know: high heels are fun, but in the long run they can hurt.” On another bright green canvas, he has painted a sparkling diamond ring, over which a silver text declares, “sometimes it’s OK to throw rocks at girls.”

Words escape Ricard in two small devotional images on view in the exhibition. In one portrait of a young boy, the artist has recast the sitter with a golden halo and a lit cigarette. The youthful adolescent meets the viewer’s gaze while exhaling a puff of white smoke. In another portrait, a found lithograph attributed to ‘MARY AT THE FOOT OF THE CROSS,’ Ricard embellishes the devout Madonna with ethereal wisps of swirling blue tobacco vapor.