Gerald Lovell

“all that I have”

New York, 392 Broadway

Garnering immediate recognition for his candid approach and heavily impastoed canvases, Lovell began painting at the age of 22 after dropping out of the graphic design program at the University of West Georgia. Frustrated by the codified, academic methods ingrained in formal arts education, Lovell utilized YouTube tutorials, his background in photography, and his tightknit, Atlanta-based community of creatives to drive his burgeoning painting practice. An avid photographer, Lovell’s interest in vernacular photography stems from a childhood in Chicago spent looking through his grandmother’s photo albums. Lovell explains “My grandmother has these huge photo albums. They're so big and detailed. She is the sole keeper of these images that document my family lineage. I grew up looking at them and they made me deeply connected to saving moments, moments that I have with people. When I started painting these were the moments I wanted to represent. I find them powerful. Painting is a grand way of continuing to document these deep moments.”

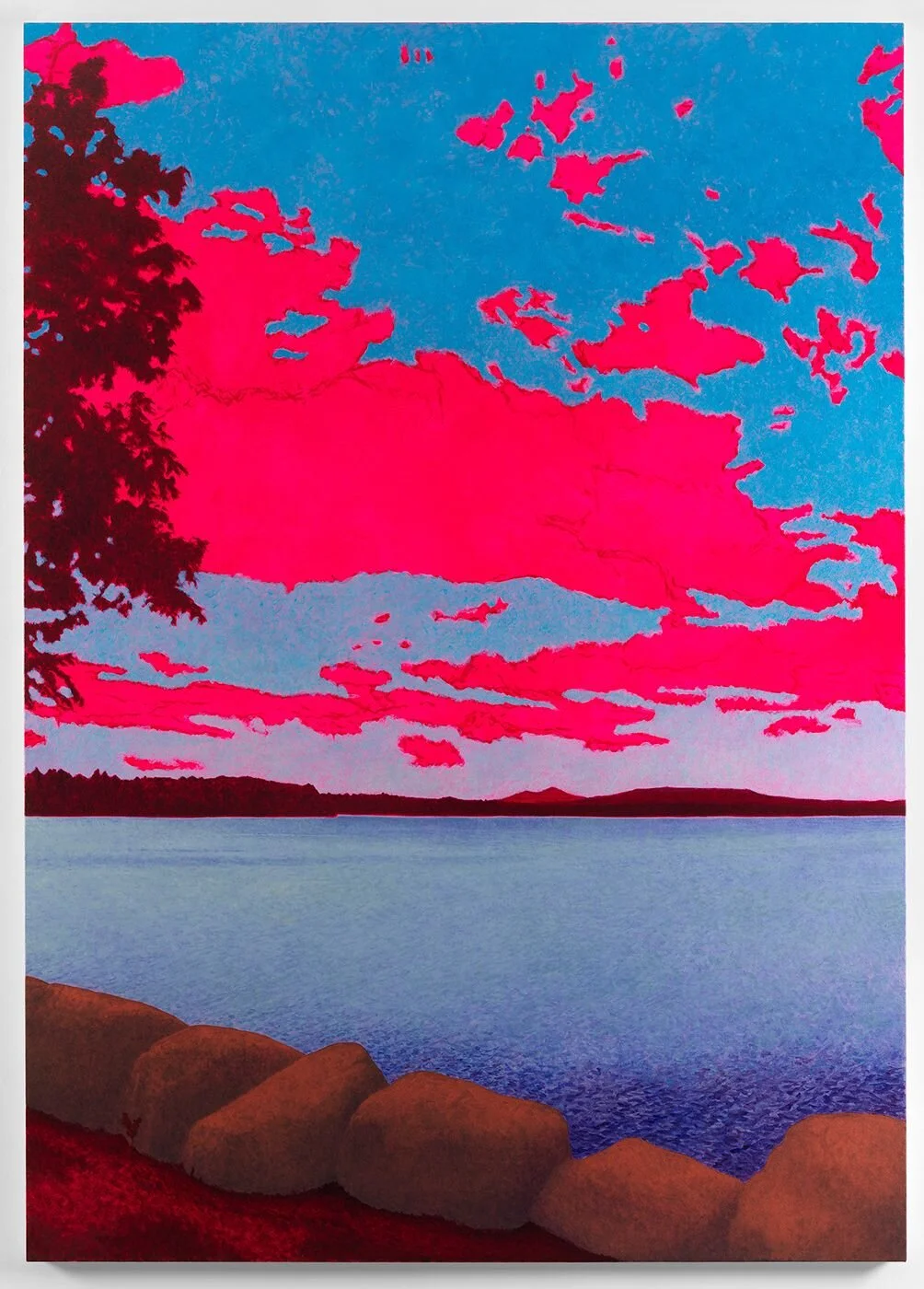

Self Portrait X, 2020 oil on panel 60 x 40 in.

For Lovell, painting is an act of biography. Combining flat and impressionistic painting with thick daubs of impasto, Lovell’s monumental portraits depict loving scenes often lost to the abyss of memory. As critic and curator Antwaun Sargent notes in his accompanying catalogue essay, works such as Park Date, 2020, of two twenty-something Black lovers tenderly embracing against a tree; The Night on the Roof, 2020, of a few girlfriends posing cheerfully, and perhaps slightly tipsy, in the small hours of a dark evening; and Troy in the Hills, 2020, of a young black male arrestingly slumping over a mailbox, refuse the notion that all Black figures put down on canvas are somehow political representations because they have gone unseen, invisible to official histories, but not each other. Informed by his deep commitment to fostering alternative community narratives, Lovell imbues his subjects with the psychical apparatuses of social agency and self-determinative power while revealing individualistic details that lay their essential humanity bare.

In all that I have, Lovell continually directs the viewer to the skin, building a fleshy materiality which becomes a site of formal confrontation and social intervention, inscribing on the surface a real reflection of the sitter’s identity that is foremost about illuminating acts of repose in spaces of intimacy. Following in the lineage of artists such as Kerry James Marshall, Alice Neel and Kehinde Wiley, Lovell captures the lived experience of both the artist and sitter in order to preserve, honor, and make visible the collective experience of contemporary Black millennial life beyond the gaze of dominant culture.