Adger Cowans

“Footsteps”

New York, 529 West 20th Street

Adger Cowans (b. 1936), has experimented with a myriad of mediums over his artistic career, ranging from fine art photography to abstract expressionist painting. His photographs exemplify the attentiveness of a curious onlooker with great affection for the visual offerings of the world; a quality that would define his works throughout his career. His work has recently received critical attention having been featured in the ground-breaking exhibition Working Together: The Photographers of the Kamoinge Workshop. The traveling exhibition, curated by Sarah Eckhardt, opened at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, traveled to the Whitney Museum of American Art, the J. Paul Getty Museum, and is now opening at the Cincinnati Art Museum.

A native of Columbus Ohio, Adger Cowans was one of the first to earn a degree in Photography from Ohio University in 1958. It was there that he studied under Clarence White Jr., the son of the legendary photographer Clarence White Sr. who is credited as being one of the early progenitors of fine art photography. It was at this time when Cowans was introduced to the works of White Sr. and the other masters of photography who also exhibited at Alfred Stieglitz’s 291 Gallery including Stieglitz, Edward Steichen, and Paul Strand, as well as to the other luminaries of the time who would greatly influence Cowans such as Edward Weston, Minor White, and W. Eugene Smith.

Adger Cowans (1936) Novella's Hands, 1970

After moving to New York City in 1958, Cowans took a job assisting Gordon Parks at Life Magazine, while he continued to define his own style. Parks would become a life-long friend and a supporter of Cowans, later referring to him as “one of America’s finest photographers.”

One of the most instrumental moments in Cowans’ career occurred while living and working in New York City during the early 1960s. Cowans was recruited by James Ray Francis to become a founding member of The Kamoinge Workshop, and along with Louis Draper, would be the only members with a formal education in the arts at the time. The Workshop was a place where members would gather, critique, and support each other personally and professionally at a time when black artists received little attention in the artistic community, and Cowans and Draper were the de facto teachers. After 60 years, Cowans still remains a member of The Workshop today, where he currently serves as its President.

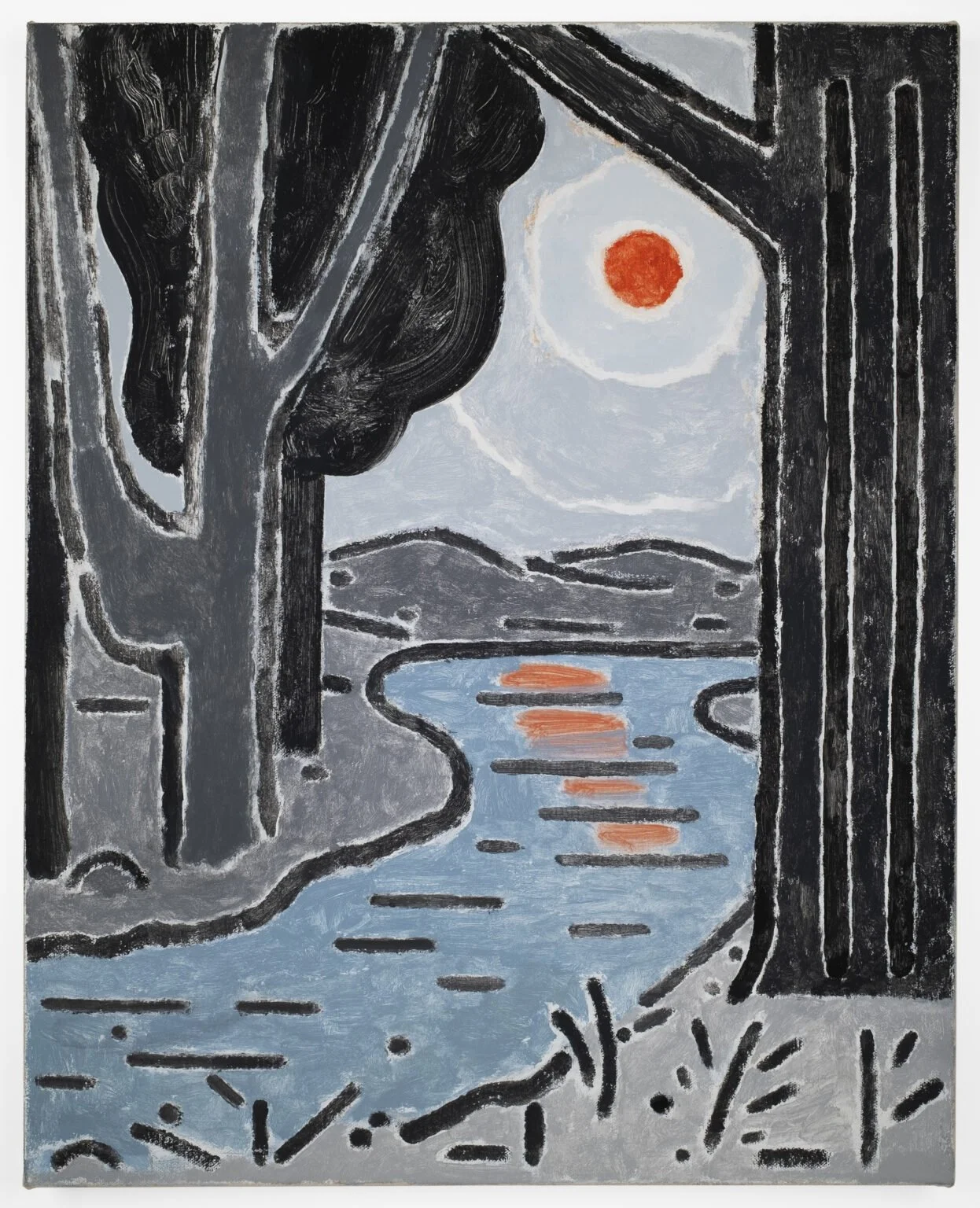

In 1979, Cowans also joined the highly influential African Commune of Bad Relevant Artists (AfriCobra), which was founded in Chicago in 1968 to use identity and style as tools to promote solidarity among the African diasporas. Cowans’ paintings stood out due to his interest in abstraction, as opposed to the more figurative work by other members, and he was among the first to use every-day tools such as combs and beveled glass squeegees to create sweeping patterns in paint. During the 1970s, Cowans would develop strong friendships with artists such as Jack Whitten, James Phillips, and most notably Ed Clark, with whom he would show together in the exhibition Sweeps & Views: Clark & Cowans.

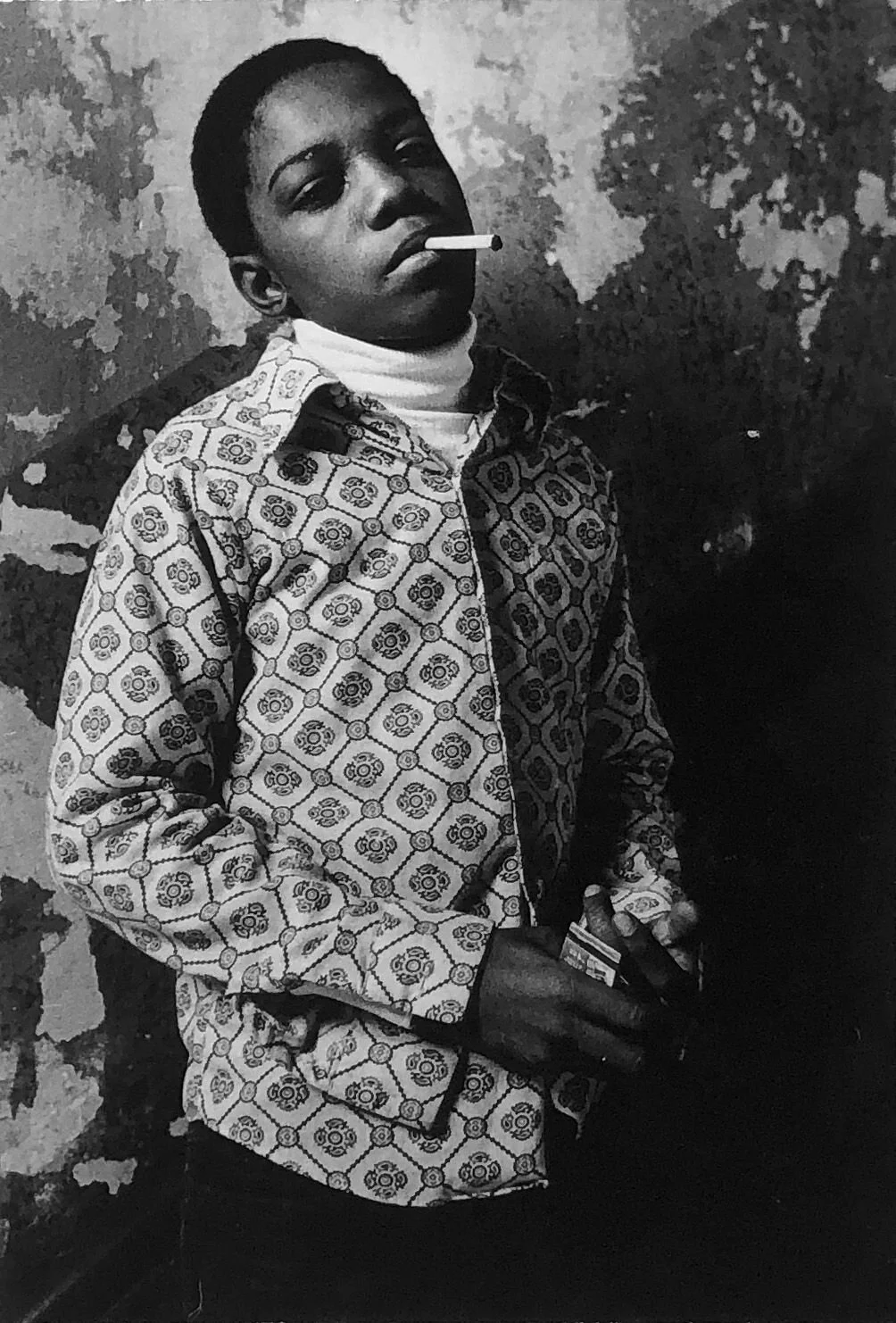

Adger Cowans (1936) Malcolm X Rally, 1963

For Cowans, the paramount elements of photography, and art at large, are emotion and feeling. Cowans describes the act of photographing as such: 'When I take a picture, I feel it. When you get that rush of feeling inside of you of 'I have it. I felt it'.' Communication of spirit and emotion are essential to Cowans’ practice, and a close second is the ability to capture light and shadow. Two exemplary images of this exploration are Icarus, 1970 and Three Shadows, 1968. Icarus depicts the blazing sun, and small human figure at the bottom of the frame, perhaps falling with melting wings of wax. Three Shadows shows three young girls walking down a sidewalk in the Bronx with their long shadows stretched out in front of them.

But perhaps the image that has come to define Cowan’s extraordinary career is Footsteps, Harlem, 1961 an image photographed from above depicting a single figure seemingly struggling to walk along a snow-covered city street. When asked about this photograph, Cowans acknowledges that many see the photograph as a metaphor for the adversity facing black Americans, but in fact, he sees it as an image representing the struggles of the human condition. Cowans states, “my images are about all of humanity. I follow in the footsteps of my predecessors whom all wanted to make great images.”