Chuck Close

“Red, Yellow and Blue: The Last Paintings”

New York, 510 West 25th Street

Since the 1970s, Close has been known for his innovative approach to conceptual portraiture, systematically transposing his subjects’ likenesses from photographs into gridded paintings. Over the course of five decades, his work challenged conventional modes of representation across a wide range of media, including various forms of painting, printmaking, drawing, collage, daguerreotypes, Polaroid photography, and tapestry. The artist posed a radical proposition with his approach to painting, going against the grain of art world trends during the late 1960s and 1970s, when Minimalism, abstraction, and seriality were dominant, and portraiture and photorealism were largely overlooked.

Chuck Close, “Brad,” 2020-2021, oil on canvas, 36” × 30.”Credit...Chuck Close, via Pace Gallery

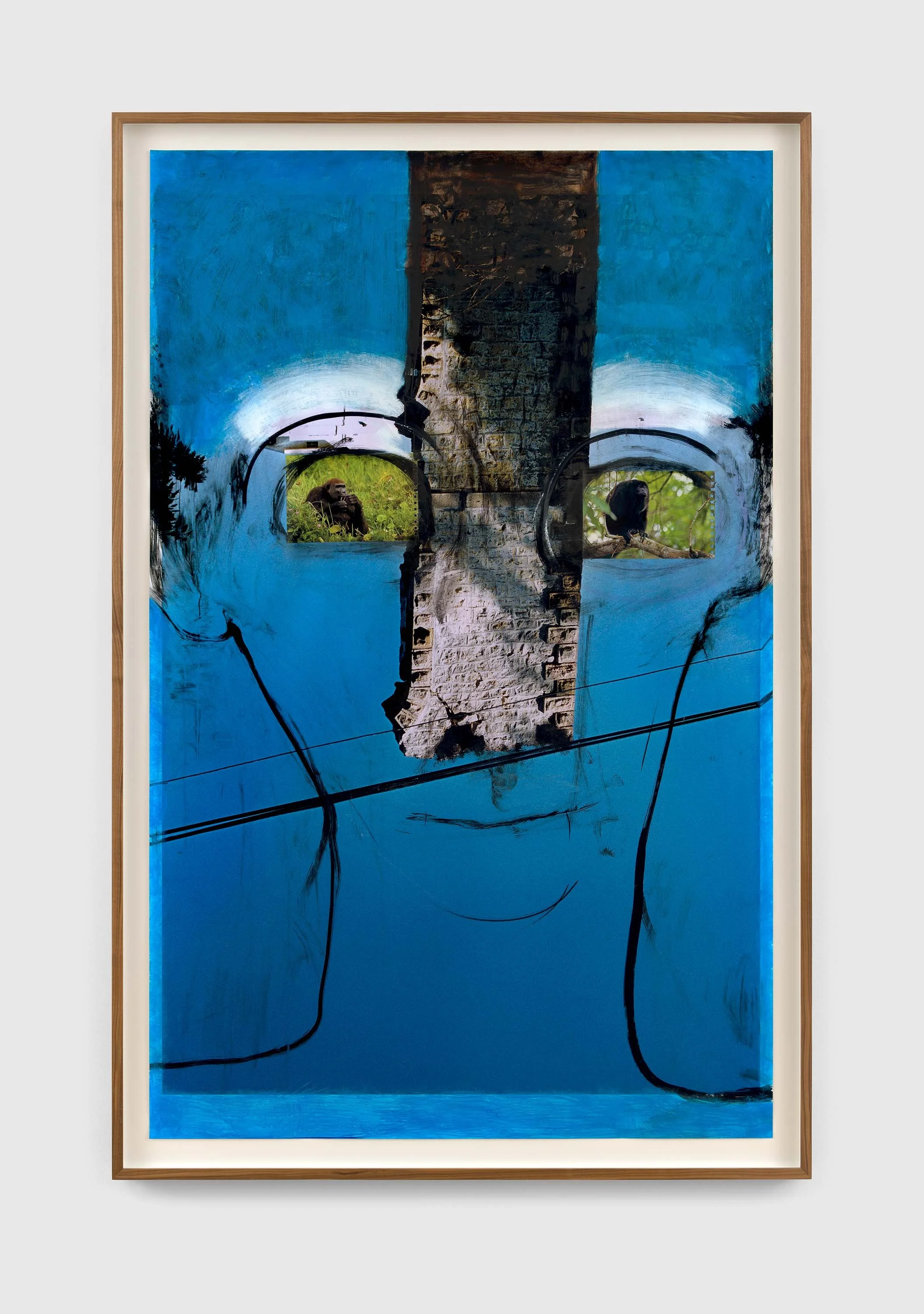

Pace’s upcoming exhibition will spotlight Close’s final body of paintings, which includes works that have never been publicly exhibited. These full-color portraits and self-portraits employ a palette of only three colors: red, yellow and blue. Layering transparent glazes of paint, Close created an effect of abstract likeness entirely different from that of his previous work. The complex color relationships that unfold in these paintings are visible at the bleeding edges of each square within the grid, where the ragged ends of each individual color are visible. Meditating on the power of color itself, Close’s final works suggest the constructive aesthetics of Impressionism, where form is built up through a chromatic architecture of brushstrokes. Appearing more abstract than representational to the human eye, the likenesses in these portraits come into greater focus when viewed from a distance or through the lens of a camera, an act of transfiguration that speaks to the artist’s interest in modes of perception and information processing.

Close realized these formal achievements in his last works while grappling with long-term health issues precipitated by a spinal aneurysm that he suffered in 1988 at the age of 48. Having lost the use of his arms and legs as a result of the aneurysm, Close was told by doctors that he would never be able to paint again. Through a grueling process of rehabilitation, he eventually regained his ability to paint by using a brush-holding device strapped to his wrists and forearms. Working through this disability for the rest of his life, he was forced to teach himself how to paint in an entirely new way, reinventing his approach to the medium in the middle of his career. In his final works, Close continued to push against the constraints of his physical disability to reinvent his own painterly language once again.

Even prior to his aneurysm, however, Close struggled with other disabilities. Throughout his childhood and adolescence, he used art as a means of navigating severe dyslexia and prosopagnosia, or face blindness. Having studied at the University of Washington, Yale, and the Akademie der Bildenden Künste in Vienna, he began teaching at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst—where he would present his first solo exhibition—in the mid-1960s. Upon relocating to New York, the artist continued to explore new modes of realism, using an airbrush to paint black- and-white, highly detailed photographic portraits of himself, his family, and his friends onto large-scale canvases, a practice he would continue for the rest of his career.