Henni Alftan

“Stop Making Sense”

New York, 549 West 26th Street

Henni Alftan’s oil paintings are often recursive, commenting on the conditions of their existence both as individual paintings and as associatively linked to one another. Working with images that are, in her words, “not realistic but offer a plausible suggestion of the visible world,” she explores how painting’s essential elements—such as color, form, and composition—can convey maximal subtext with minimal visual information. The works in Stop Making Sense both propose continuity and refute it, with certain canvases echoing and framing the other as they revel in the tensions created when an image’s promise of wholeness is disrupted.

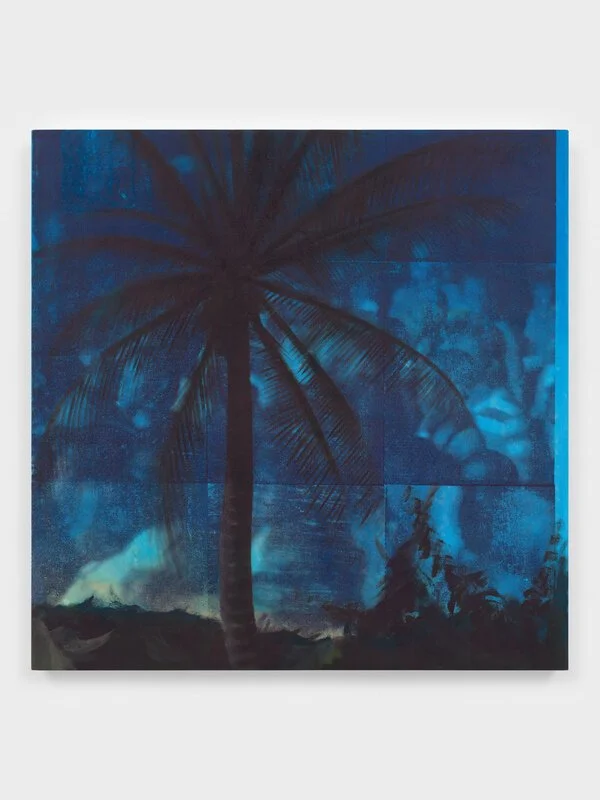

In Alftan’s renderings of portals and mirrors, space is flattened, compressing image and substrate into a single surface: we can rarely see through them, and when we do, the subject on the other side has been transformed into motif rather than representation. In Electric Light (2024), geometric blocks of color reveal themselves to be windows through contextual clues, rather than the transparency of glass: a grid of pastel light obscures any glimpse into the goings-on inside the building that is the subject of this image. The cool glow of the monochromatic screen in TV(2024) could be the culprit, but Alftan only offers images, never explanations. A concentrated beam of luminous yellow rays stream through Arched Window (2023), while the titular subject’s shape rhymes with a window in Karma’s Chelsea gallery.

In her paintings of figures, Alftan often represents the body in fragments, withholding totalities to prompt the viewer to fill in the blank space with their own imagination. The diptych Black Umbrella (In-between) (2023) is hung such that the gap between the two panels, each of which depicts one side of a person in a red sweater protecting themselves from rain, occupies the area where the figure’s face would logically fit—as such, any sense of identity is denied. For Knees (2024), Alftan crops in closely to a pair of crossed legs, painted as continuous fields of peach and spotted with blurry purple bruises that index an earlier, unseen accident. Cigarette (Déja-vu) (2023), another diptych, portrays a cigarette when it is first lit and again once it has burned down. The bright-orange cherry grows as the rest shrinks, visually representing the passage of time. These close-ups and moments when time jumps forward reflect the influence of the cinematic concept hors-champ, or that which happens off-screen.