Ouattara Watts

“’90s Paintings”

Karma

New York, 22 East 2nd Street

Over the course of the past four decades, Ouattara Watts has created densely layered paintings embedded with a kaleidoscopic range of materials and symbols. In his often-monumental works, numbers, fractals, and otherworldly forms painted by the artist are brought into relation with sacred objects, photographs, and textiles gleaned from flea markets. Watts’s syncretic approach also pulls from his studies of Picasso, Baudelaire, and Surrealism, his African heritage, and his interest in Egyptology, among other cultures from around the world. The five paintings from the 1990s exhibited here are key waypoints in the development of his idiosyncratic artistic language.

Spurred by a fortuitous 1988 meeting with Jean-Michel Basquiat in Paris, Watts, who was then living in the French capital, settled permanently in New York in 1989. In the next ten years, he would be included in the 45th Venice Biennale; receive his first solo museum exhibition, curated by Lawrence Rinder and hosted by the Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive; and befriend curator Okwui Enwezor, who wrote in 1995 that Watts was “rewriting and reinscribing the position of African artists in modern art history.” This pivotal decade culminated in an invitation from Enwezor to participate in documenta 11, an iteration of the exhibition now famous for its non-Eurocentric curatorial bent, and his inclusion in the Whitney Biennial, both in 2002.

Installation view, 22 East 2nd Street New York

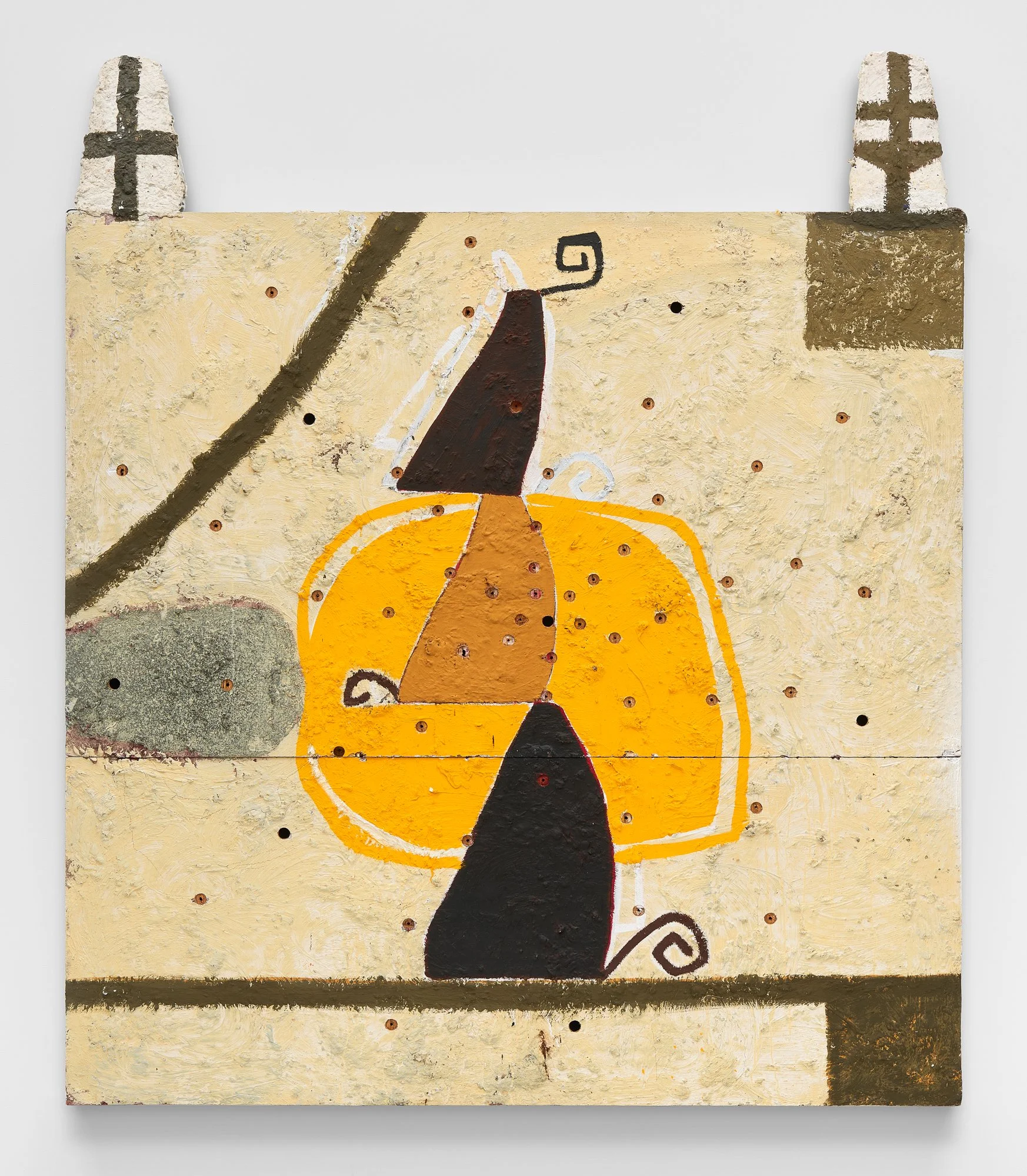

Pythagor and Thot (1990) was first shown in Watts’s inaugural New York solo presentation, a 1990 outing at Vrej Baghoomian, Inc. in SoHo. In Pythagor and Thot, Anubis, the Egyptian god of the underworld, rides in a boat on a river schematized as black triangles. A lantern lights his way and an ankh, symbolic of eternal life, hangs behind him. The work represents a journey to the underworld and back, like the Greek myth of Orpheus and Eurydice, and parallels Watts’s two journeys across the Atlantic: the first, when he traveled with Basquiat to New Orleans for the jazz festival and to see the Mississippi River Delta, and the second, when he moved to New York for good. The triangular waves and essentialized forms emerge in part from Watts’s interest in Kazimir Malevich and other European avant-gardists of the early twentieth century, while the nailed-on panel connects Pythagor and Thot to Watts’s other extensions of his canvases into the realm of architecture.

The triptych Sacred Painting, from the same year, is a prime example of the artist’s sculptural tendency during the 1990s, an approach that led art historian Robert Farris Thompson to deem him “the black architect, the builder of the city of the twenty-first century, a city of reunion, of association, and not of division.” To create the work’s arcing marks, Watts applied paint thickened with leaves to the panels as if building up the facade of an earthen building. A lighter-hued ridge running along the top of Sacred Painting juts out from the picture plane. The monumental work is pierced through with holes, calling attention to its three-dimensionality, while a doorway-shaped cutout invites the viewer to step into the constructed space. Aluminum containers, likely salvaged from New York’s streets, hang from the rightmost panel, while “347,” one of the city’s area codes, is inscribed at the top of the composition. Explaining his sculptural approach to his medium in 1993, Watts said: “If you are born in Africa, sculpture and painting are the same.” For Sacred Painting and other works, the artist found inspiration in not only African architecture but also in the work of Mark Rothko, whose paintings, like Watts’s, draw viewers into their implied depth.