Nikki Maloof

“Skunk Hour”

Perrotin

New York, 130 Orchard Street

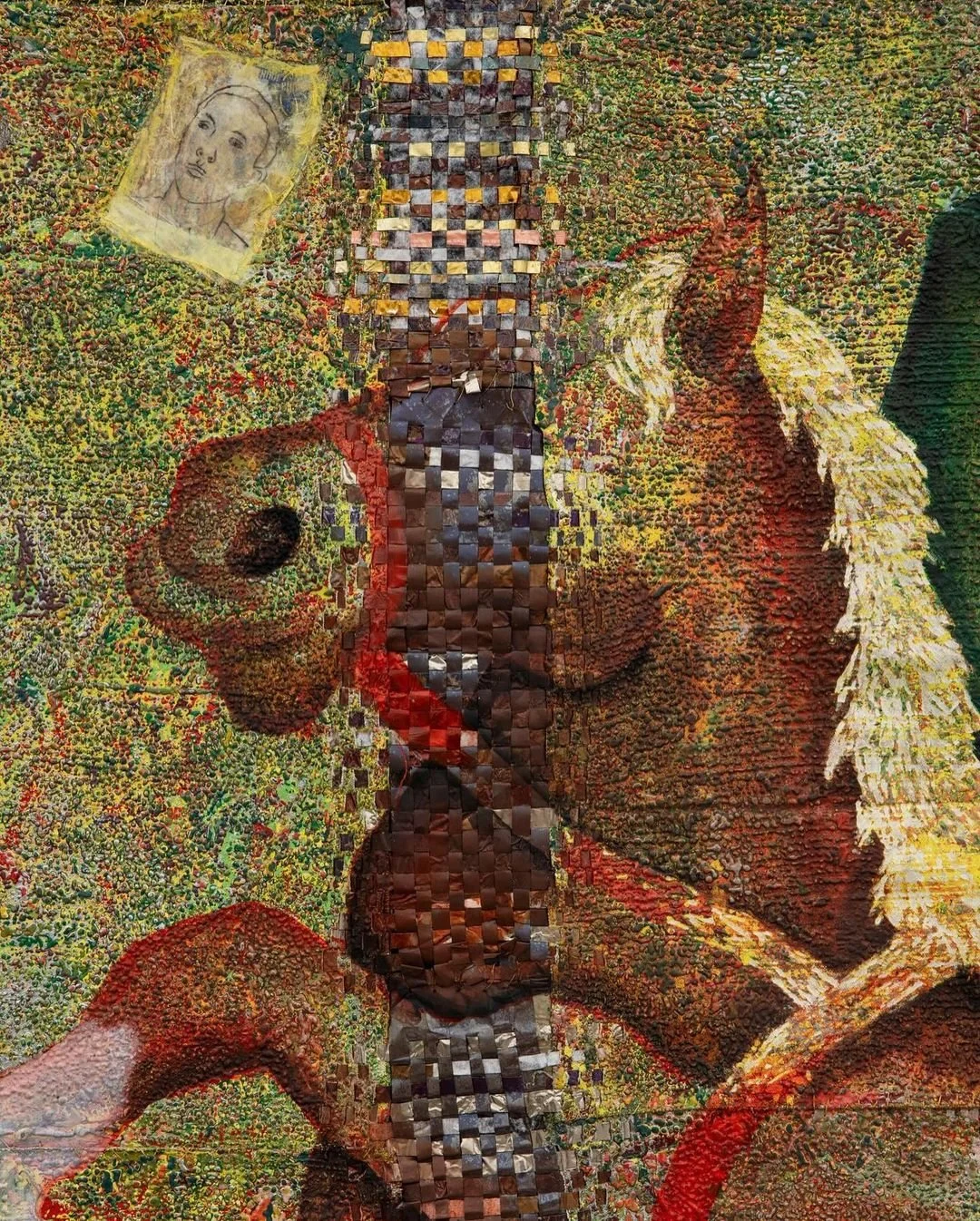

For Nikki Maloof, painting is a way to convey the experience of existing in the world—the light, the dark, and all the shadows in between. Her language is figuration: she started out with portraits of individual animals, progressing onto still lifes and, most recently, domestic interiors and landscapes populated with a mix of creatures—human and non-human; alive, dead, and inanimate. These subjects, on one level, have an everyday familiarity. Indeed, they are in many instances collected from Maloof’s immediate environment: for the past few years, her house and studio in rural Massachusetts. But the resulting depictions, however vivid, never feel quite real.

Installation View, Courtesy of Perrotin

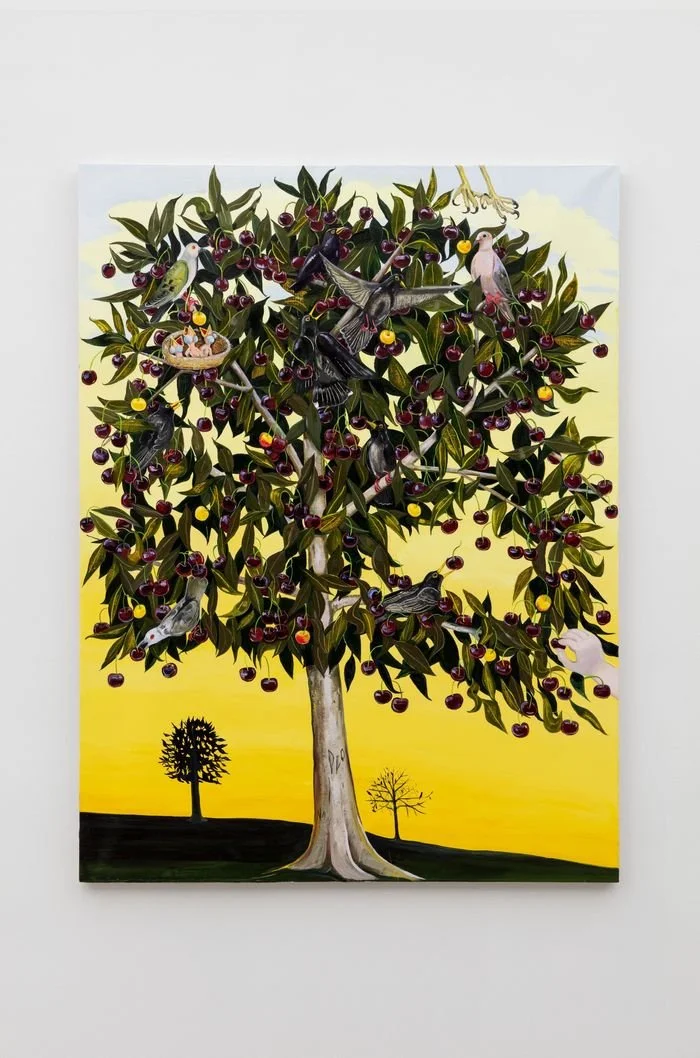

The colors are bright, the shapes cartoonish, the compositions often implausible. Everything is emotionally charged. The eyes of dead fish seem to brim with sadness, the oversized blade of a knife glints with menace. A woman who shares Maloof’s physical features stands at a window with a glum expression, her face only just visible behind a tree dense with apples. Looking at these canvases is like looking at a series of dreams, governed by a mysterious logic, their characters and events freighted with ambiguous symbolism.

Of course, unlike in a dream, Maloof chooses what to paint: hers is a conscious artistry. We see evidence of this in her equally accomplished graphite works on paper, in which images are carefully worked out before she embarks on the larger oils on linen. (It’s fun to play spot the difference between the versions in pencil and paint: notice how a glass of wine materializes on a countertop; how a cat relocates from the landing to the stairs.) Perhaps her work is more akin to confessional poetry, intensely personal yet meticulously crafted.

The title of this exhibition, “Skunk Hour,” is borrowed from a well-known poem by Robert Lowell, published in 1959, which begins as a light-hearted description of a seaside town in Maine and culminates in a self-portrait of a mind in turmoil. “I myself am hell,” wrote Lowell, “nobody’s here— / only skunks, that search / in the moonlight for a bite to eat.” Similarly, Maloof describes the scenes she constructs as “vessels,” giving tangible form to psychological states or particular thoughts and feelings.