Zorawar Sidhu & Rob Swainston

“Doomscrolling”

New York, 35 E 67th Street

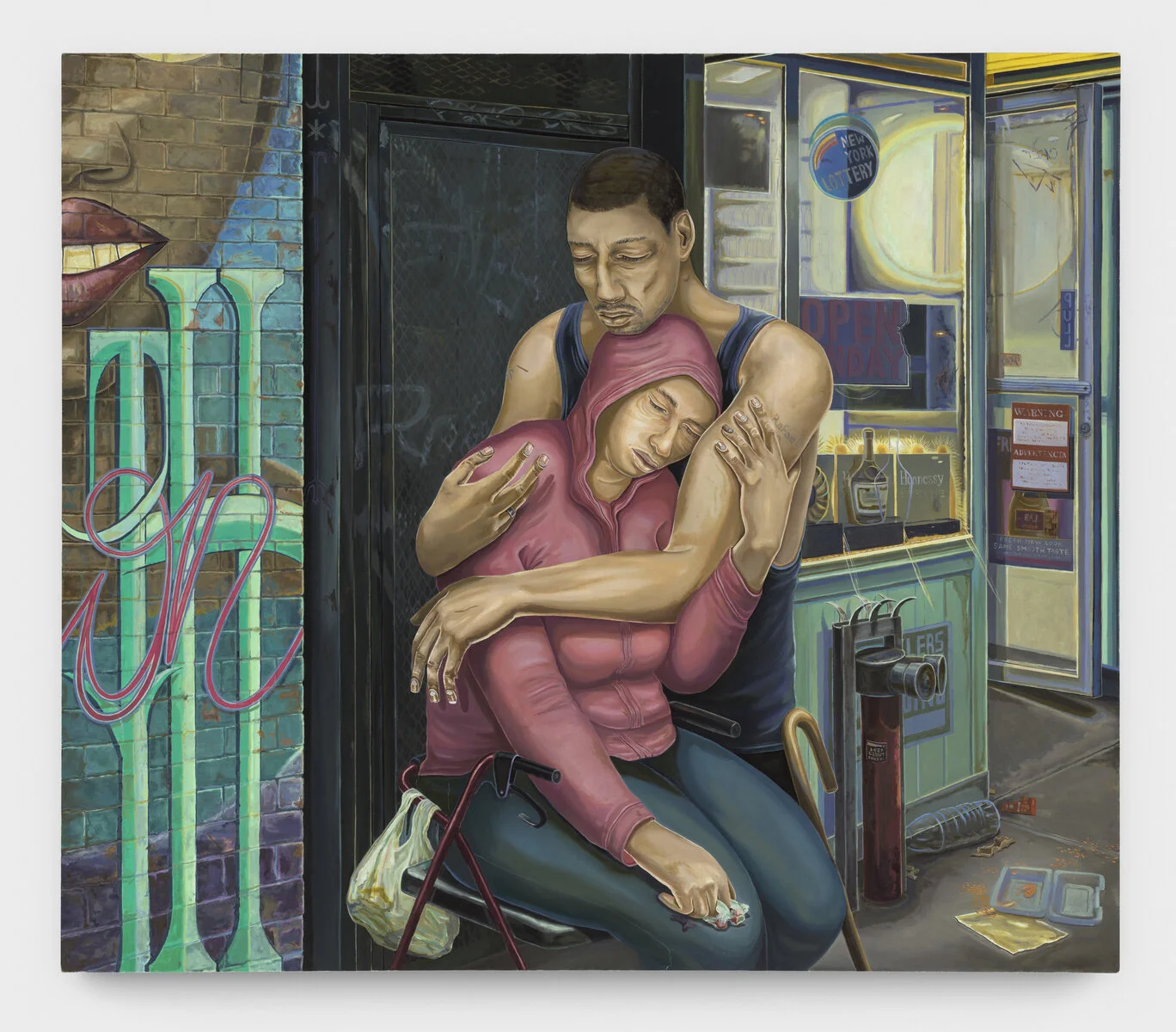

Doomscrolling, a relatively recent activity induced by disturbing, perhaps mind-bending, current events, is “the act of spending an excessive amount of screen time devoted to the absorption of negative news. Increased consumption of predominately negative news may result in harmful psychophysiological responses.” This exhibition takes its title and inspiration from this newly diagnosed and addictive compulsion.

At the start of the pandemic “I went out every morning on my bike and was photographing Manhattan, but it was empty,” says Swainston, who, like most of us, was experiencing all the hope, anxiety, and fear about everything that was happening in 2020. “We were just like everyone else, obsessed by consuming images of it. All of a sudden, plywood went up on buildings around the city and then I realized the potential of it: Letting something that happened in 2020 be carved onto the plywood used to cover up Manhattan.” The artists contacted various institutions. Several allowed them to come and take their plywood. “Because the plywood was outside, it collected graffiti on it and was weathered by the elements, which is still visible in the prints,” says Sidhu.

Swainston and Sidhu collected approximately 120 sheets of plywood. “We are depicting events that are dirty and messy. Having the plywood distressed is a part of the story. The show really comes out of our own ‘doomscrolling,’” Swainston says. Sidhu echoes, “It was an experience of terror through viewing the media of it all.”

Doomscrolling is comprised of 18 moments between May 24th, 2020 and January 6th, 2021, the day of the insurrection at the United States Capitol in Washington, D.C. These dates are tied to iconic images and specific events: The May 24th New York Times cover “U.S. DEATHS NEAR 100,000, AN INCALCULABLE LOSS”; the next day George Floyd is murdered; the day after that the protests begin; Kyle Rittenhouse shoots three people during the protest in Kenosha, Wisconsin; Donald Trump holds the bible upside down after the D.C. Park Police teargas a group of peaceful protesters; the militarized police vehicles; the protestors with their hands up.

“The first print we finished was January 6th. So many of these images seem out of place and out of time—and they just don’t even really seem possible,” Swainston says. He and Sidhu have chosen to represent each date as a montage of events to convey the conflicts of ideologies, physical violence, and meanings of these events that are still being negotiated. “If we let them remain only as images we doomscrolled in 2020, they become fixed in the past,” the artists say. “We can be indignant or hopeful about them, but there is nothing we can do. By reconsidering them as montages we are keeping them in the present as ongoing issues, keeping their meanings unfixed, and keeping open the possibility for real social change.”

To create the montage effect the artists overlay image upon image, as if scrolling through a computer screen or mobile device. Each image resonates with the ones before and after it, giving dimensionality to the works. Sidhu and Swainston employ art historical references such as rays of light from Albrecht Dürer, hands from Käthe Kollwitz and heavy shadows from Edvard Munch.