Daniel Arsham

"Time Dilation"

New York, 130 Orchard Street

The most amazing machine on earth is buried outside Geneva: the CERN Large Hadron Collider. It is a huge, perfectly circular tunnel in which particle beams converge at near-light speeds, a task (according to CERN’s website) that is “akin to firing two needles 10 kilometers apart, with such precision that they meet halfway.” The collisions allow for the study of the most elusive aspects of physics: among them, the possible existence of dimensions beyond space and time.

CERN’s operations and Daniel Arsham’s career have been roughly contemporaneous, rather like Einstein’s Relativity and Cubism. Arsham is no scientist, but his quarry, too, is the nature of temporality itself; and he applies a pin-sharp exactitude to his many experiments. For the present exhibition at Perrotin, he has brought together multiple pathways of his creativity, groups of objects that would usually remain discrete. It’s another type of collision. And it warrants analysis.

Cave of the Sublime, Iceland, 2020. Acrylic on canvas panel. 84 x 120 x 3 in. Photo: Guillaume Ziccarelli. Courtesy of the artist and Perrotin.

The exhibition’s most striking encounter is the one that Arsham stages between classical statuary and Pokémon, the latter of which marks the first major collaboration between a contemporary artist and the storied Pokémon company. Here, both are subjected to the artist’s signature decay. It’s as if he were enacting the half-life of these icons: trophies, meet entropy. The classical works are drawn from Arsham’s collaboration with the august RMN-Grand Palais, in Paris (also featured in his exhibition “Moonraker” at the Musée Guimet), while Pokémon is Pokémon. Two different cultural universes, in a highlow, head-on crash. Or is it a crossroads? Two trajectories arriving to the same point: ancient sculpture is so venerated that it has become cliché, the stuff of museum gift shops, while the creatures of Pokémon, which seem to be influenced by Japanese mythology, have morphed into their own 21st century version of the sacred.

This is the sort of convergence that fires Arsham’s imagination: he is a connoisseur of collapse, an impresario of implosion. Witness the new resin works that he announced to the world via Instagram on November 19, with the unimprovable caption: “Multiverse, entropy layered, dimensional alternative, possibility device.” Four different ways of saying the same thing, you’ll notice, and that leitmotif of overlay is present in the works themselves. Their constituent elements –a magazine, say, with a camera, a videotape, and a box of breakfast cereal – lap one another, each washed up on a different tide. The use of transparency and gradient color gives the works a distinctly digital tang. While entirely analogue (in fact, they were inspired by resin casting molds in Arsham’s studio), they commune with the virtual; they seem to have absorbed the evanescent qualities of the 21st-century commodity form. They are physical manifestations of hyper-reality.

That last term is one that began circulating back in the 1980s. It has only become a reality more recently, with Arsham as one of its primary avatars. Something similar could be said for the concept of ‘time-space compression,’ popularized in The Condition of Postmodernity (1990), by by the cultural theorist David Harvey. He postulated that technologies of transport, communication, and media had brought about an ever-increasing speed, and hence, a sense of proximity and instantaneity; and furthermore, that these effects would have “a disorienting and disruptive impact upon politicaleconomic practices, the balance of class power, as well as upon cultural and social life.” Sound familiar?

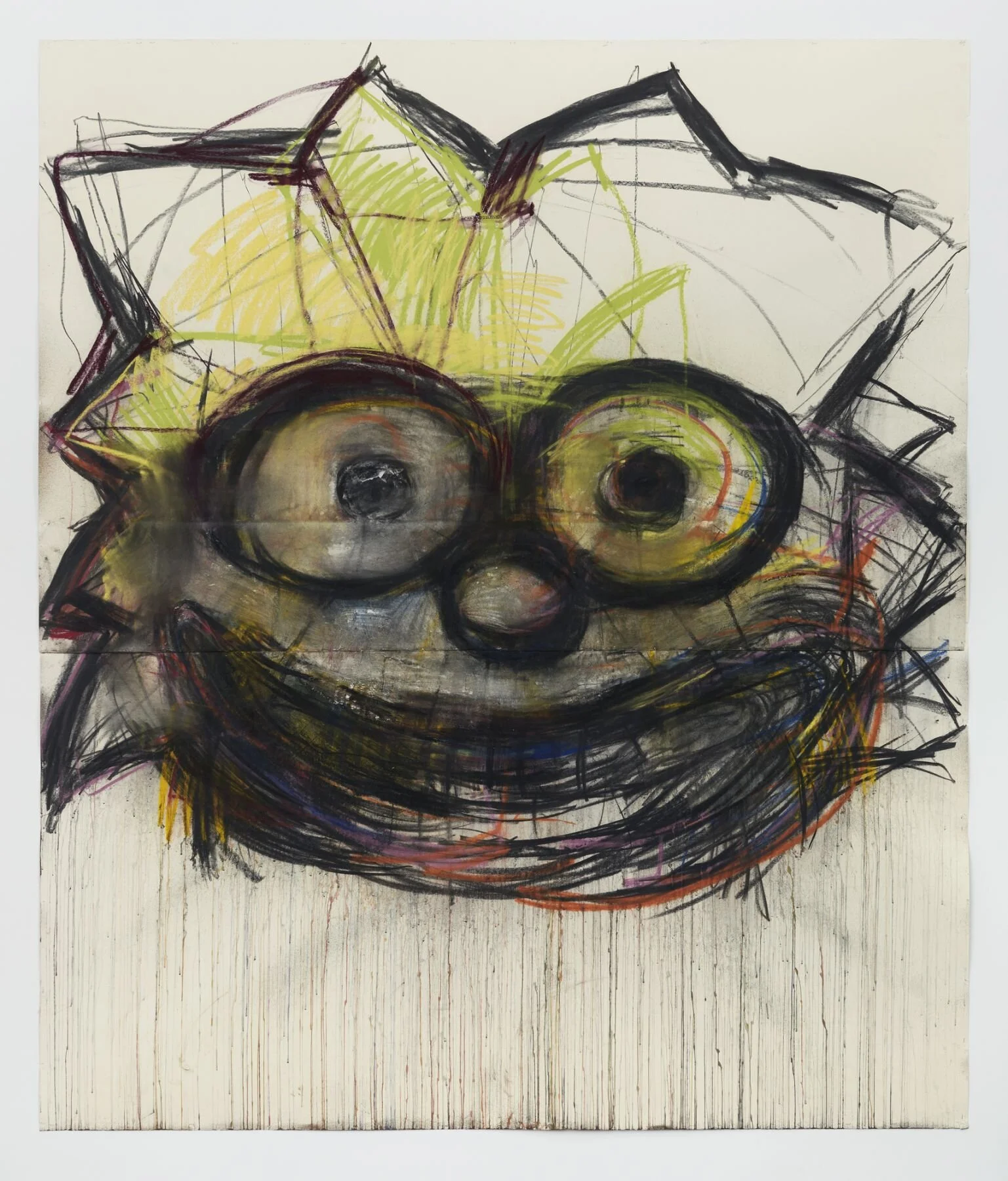

If Harvey’s book reads, in retrospect, like a front-line report from the present, then Arsham’s work explodes our furiously time-space-compressed era outward, into a Big Bang of narrative possibilities. The paintings included in the present exhibition are the perfect vehicle. They may be a surprise to some, who have come into contact with Arsham only in the past few years. But he was trained as a painter, and the first works he showed with Perrotin were in this medium. The disrupted circumstances of 2020 all but forced him back to the easel, as social distancing made his usual studio operations impossible. Suddenly it was just him and the blank canvas.

His response, in this down-tools moment, attests to the depth of his inner artistic resources. After first laying out his images, he transfers them manually to the canvas, employing a special formulation of acrylic, super-matte with a high pigment load. Because the pictures are monochromatic, they have something of the character of photographs, but also a rich texture, an assertive materiality. As for the images – they are like a visit to the cathedral of his mind, a psychic spelunk. Sublime caverns open up to our view, populated by classical figures depicted at disconcerting scale. We are in the cave, here. This is what we find when we go back to the origins of history, or imagine how it all will end, from Lascaux to Plato’s Republic to the Fortress of Solitude, from womb to tomb. Our present hangs, crystalline, multi-faceted, and oh so fragile, somewhere along that ambit; one that Arsham alone seems to traverse, round and round on the track of time. —Glenn Adamson