Noplace

“Noplace”

New York, 535 West 22nd Street

In Utopia (1516), the English lawyer, social philosopher, author, statesman and Renaissance humanist, Sir Thomas More coined the term ‘Utopia’ in his sociopolitical satire. Combining the Greek words “not” (ou) and “place” (topos), 16th century readers would have translated the new word to ‘Not place’ or ‘Noplace’. More’s Utopia was an imaginary arcadian paradise, off the coast of an inexact location in the ‘New World’. Describing this Utopia as the blueprint for a perfect society, More conceived of a place that offered the material benefits of a welfare state, promoted religious freedom, tolerated euthanasia as well as divorce, and abolished the societal constructs of private property, monarchy, and military.

Written against the backdrop of the tyrannical reign of King Henry VIII, Utopia sat in stark contrast to its societal context, which was without freedom of speech or thought, where one man accrued vast wealth, while thousands of others starved. By naming the island ‘Utopia,’ or ‘Noplace’, More emphasized the island’s non-existence, allowing him to discuss real monarchical corruption, while preserving his head (which Henry VIII put on a spike in 1535). By creating a fantastical positive ideal, More communicated the injustice of his lived reality while simultaneously making an appeal to humanity’s capacity for change.

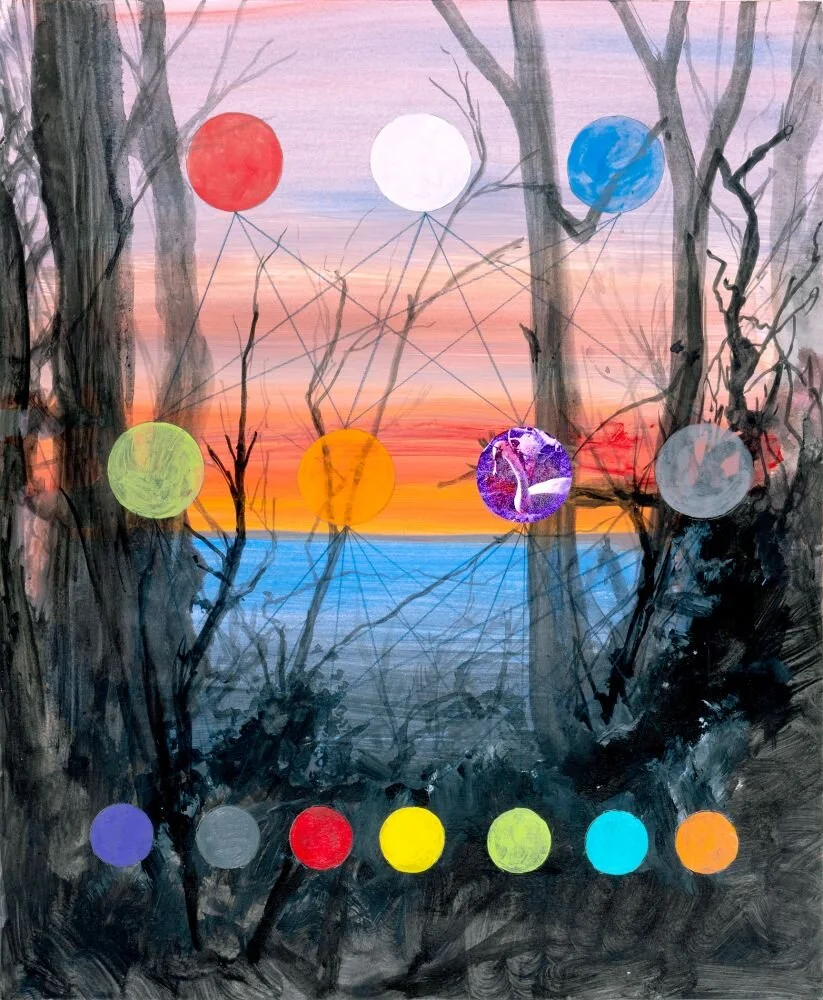

Devin N. Morris abstracts American life and subverts traditional value systems through describing the puzzle of existence, examining racial and sexual identities in collaged two-dimensional and three-dimensional objects. Creating elaborately constructed environments using commonly found household materials and fabrics, such as carpets, wooden furniture, lamps, and windowpanes, Morris’s surreal landscapes combine grandparents’ living rooms, church pews, funeral home parlors, and hospital waiting rooms in a puzzle of memory. For this installation Morris looks specifically at the black body, showings its matriculation through space as fragmented, filled with many dialects, and constantly rearranging and often speaking in translation.

Devin N. Morris Water not under the moonlight, water at moon’s eve. Saw it from behind and now the cold front is unveiled, guiltily picked and exposed., 2020 acrylic, painters tape, wall paper, plaster, wood veneer, wood moldings, house paint, oil pastel, pastel, collage, ink, door, vinyl, wool, daily vitamin, acidophilus, velvet, wood shutter, footboard on panel

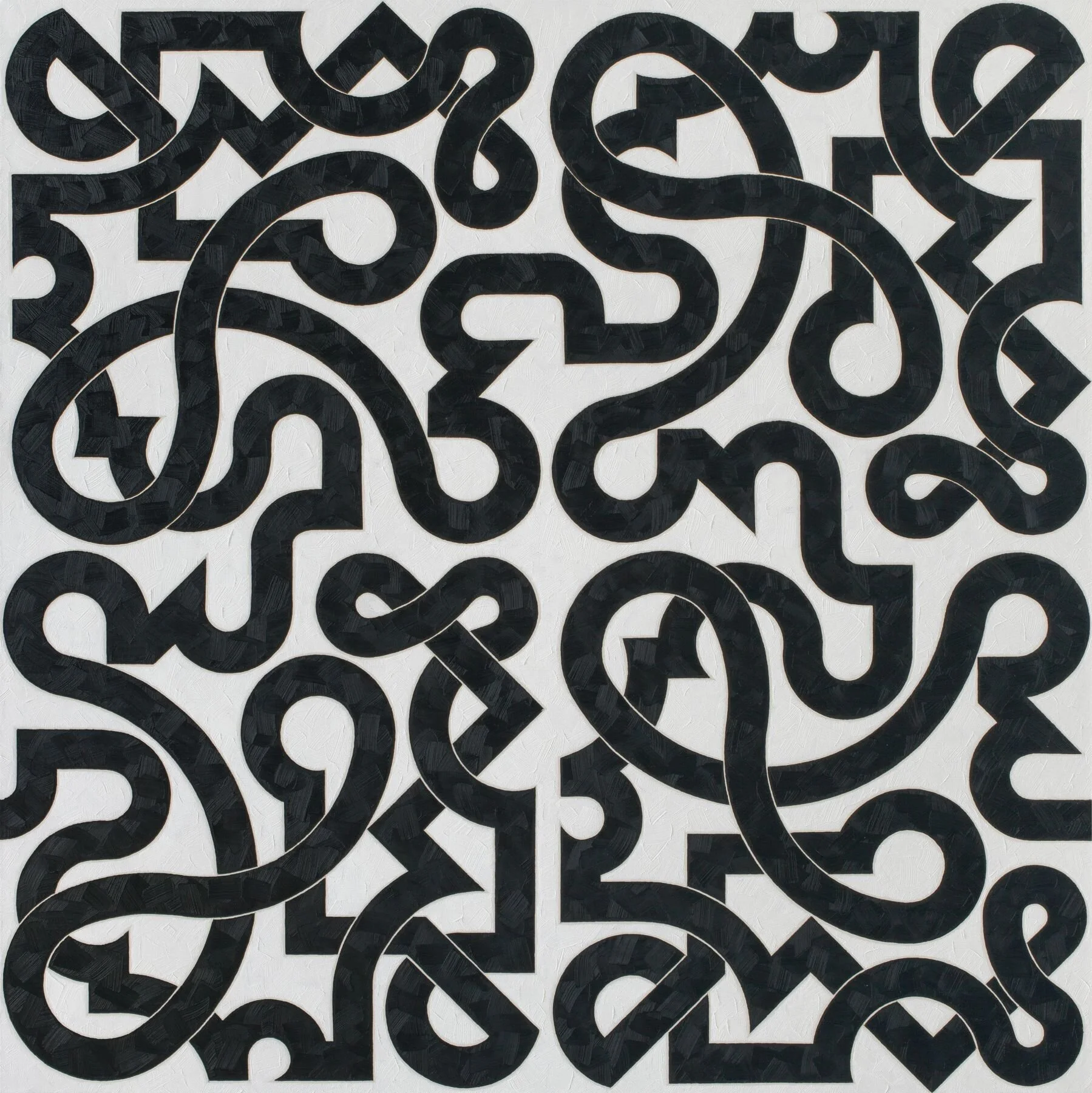

Joel Dean creates symbols that reflect the contaminated cosmos of the American Dream. Late last year, Dean began a series of letter paintings based on drop caps, the enlarged initials of Medieval illuminated manuscripts, that are today more commonly associated with fairytales and fantasy narratives. These paintings represent the condition in which a letter, once a single unit of information, becomes an enigmatic and multitudinous pictorial vessel. Beginning each with the form of a single letter, Dean intuitively transforms the initial shape into an inhabitant of its own expanded world over several months. Depicting each letter in an entangled mix of organic growth and man-made mechanisms of industrial expansion, Dean’s paintings highlight the structural and visual parallels between written systems and the complex worlds they describe. Dean’s imagined constructions give meaning to the isolated letters, just as the letters initially informed the evolution of the surrounding imagery.

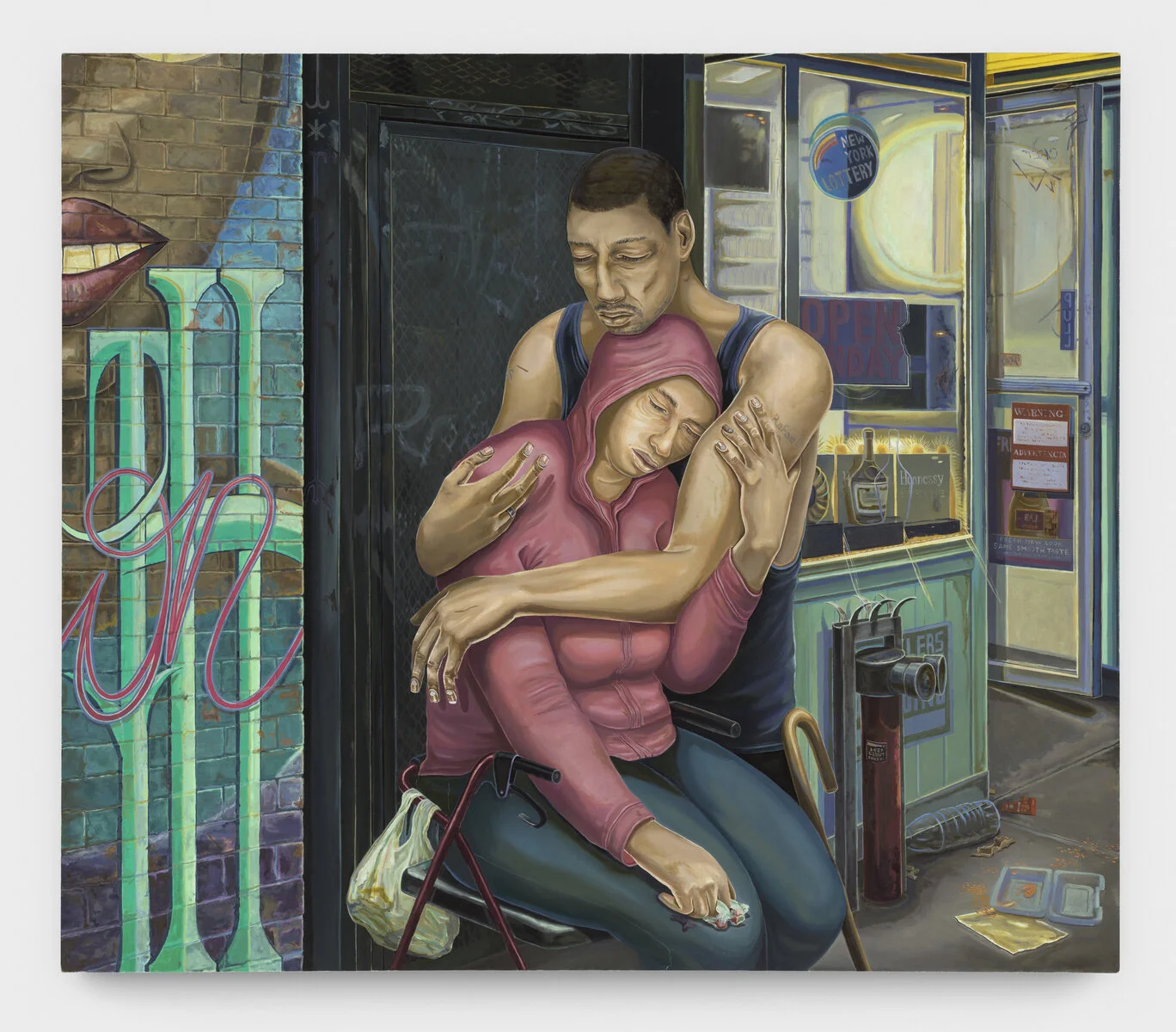

Combining histories of pre-colonial Central America, personal mythology, and collaborative rituals, Guadalupe Maravilla’s Disease Thrower #4 functions as a headdress, instrument, and shrine. Through the incorporation of materials collected from sites across Central America, anatomical models, and sonic instruments such as conch shells and gongs, Maravilla describes such sculptures as “healing machines”, ultimately serving as symbols of renewal, generating therapeutic, vibrational sound. Throughout the exhibition, Maravilla will perform weekly sound baths for groups of five to seven visitors.

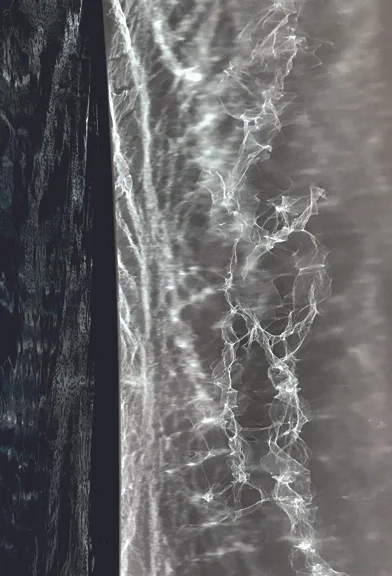

In largescale painted plexiglass sculpture’s punctuated with diaristic narrative etchings, Raque Ford envelops her audience, folding their reflections into a material and emotional drama. Exploring narratives of black female identity through constant juxtaposition, Raque Ford’s work lives between abstract and personal, masculine and feminine, lightness and darkness, and timidity and aggression.

Ficus Interfaith That Hideous Strength, 2020 cementitous terrazzo, zinc, brass, walnut, various veneers 30 3/4 x 48 inches (width, opened)

Ficus Interfaith is a collaboration between Ryan Bush and Raphael Martinez Cohen. As much a research initiative as a sculptural practice, Ficus Interfaith pursues projects that focus on their personal and collective interactions with the “natural” by way of relearning production methods that investigate ingenuity and novelty as it emerges from craft. Using terrazzo, a composite material consisting of leftover marble, glass, and other waste, used to make decorative floors since antiquity, Ficus Interfaith embraces the spirit of collaboration and reuse. In Noplace, the duo will present a terrazzo triptych depicting a fire overwhelming the hearth of a nonspecific domestic interior, its flames licking the frame of a generic landscape painting hanging overhead. Such works operate as metaphors for other worlds, and ultimately become portals with the potential to activate the viewer’s imagination in the present.