Mamma Andersson

“The Lost Paradise”

New York, 533 West 19th Street

Characterized by a unique combination of textured brushstrokes, loose washes, stark graphic lines, and evocative colors, Mamma Andersson’s works embody a new genre of landscape painting that recalls late nineteenth-century romanticism while also embracing a contemporary interest in layered, psychological compositions. Her often-panoramic scenes draw inspiration from a wide range of archival photographic source materials, filmic imagery, theater sets, and period interiors, as well as the sparse topography of northern Sweden, where she grew up: mountainous backdrops, trees, snow, and wooden cabins are recurrent elements within her works. Yet, rather than conveying specific spatial or temporal reference points, they revolve around the expression of atmospheres and subjective moods, and frequently appear to merge the past, the present, and the future.

On view in the exhibition will be a body of work from 2018–2020 that opens new perspectives on a selection of motifs from throughout the artist’s career: barren branches and thick-barked pine trees, domestic interiors, horses, and young women. Across these recent compositions, Andersson engages with themes of femininity, fantasy, and memory, recalling moments and emotions from her own childhood while also invoking what lies ahead. This is particularly evident in a trilogy of works entitled The Lost Paradise I–III (all 2020), which depict women walking with their backs to the viewer. Their tall riding boots inevitably draw attention to the absence of equestrian companions, in turn emphasizing the isolation of the figures within empty landscapes of either scorched or black earth and dark, thick clouds. In a symbolic gesture, the sun has moved from the sky onto the backs of their jackets, implying an uncertain road in front. Acknowledging the paintings as a form of self-portraiture, Andersson has noted that these works broadly address “a postwar period when we lived in innocence with the future ahead of us and not behind us.”1

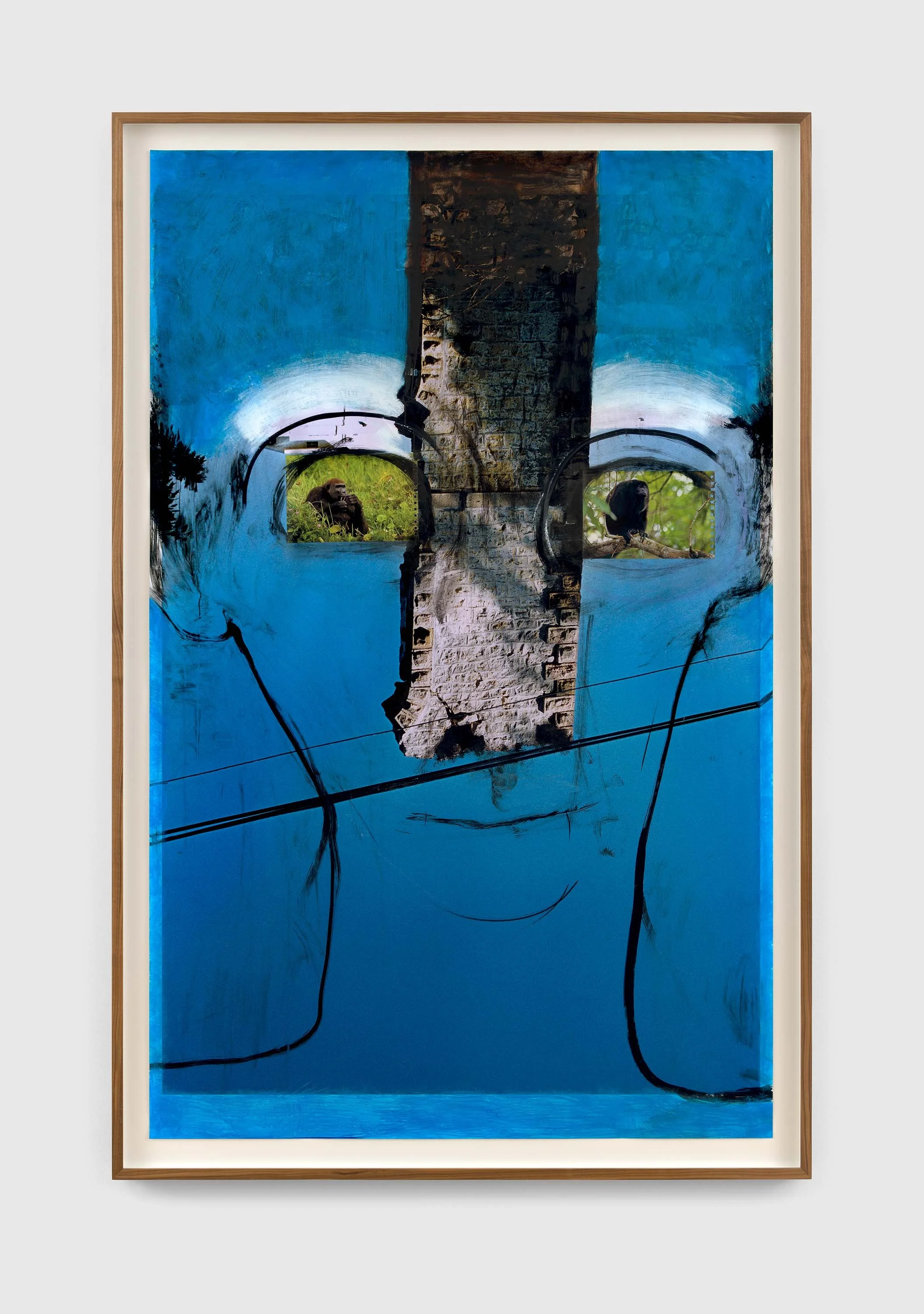

Youngster (2018) depicts a young woman saddled atop a large, dark-brown horse, her downward gaze aptly conveying the emotional complexity and inexplicit longings of childhood. Intrigued by the profound relationships sometimes formed between girls and horses, which the artist herself yearned for as a child but did not experience directly, Andersson subtly captures the contradictions of vulnerability and strength, and innocence and power, as well as an erotic subtext of attraction, desire, and guilt. In other works, including Silent Dawn, Old Hat, and Wood Cut (all 2019), highly detailed, closeup views of bark emphasize a non-narrative dimension, emerging rather as manifestations of a state of mind—the deep melancholia, perhaps, that sometimes results from the region’s long, dark winters and short, bright summers. In the latter two works, juxtapositions between hollow areas and tree trunks indirectly suggest a male/female dichotomy.

Gender dynamics, along with an analytical, introspective atmosphere, are also apparent in Pull My Daisy (2018), where a woman, turning her back to a male companion, faces an interior wall; as well as in Echo (2018), in which deep shadows merge with antique objects in the corner of a living room. Both compositions resemble still lifes, thus furthering a tradition of quiet, dreamlike domestic scenes by Scandinavian artists such as Vilhelm Hammershøi (1864–1916) and Edvard Munch (1863–1944). A quiet, serene mood is similarly presented in Lull (2019), where two horses graze on snowy grounds outside a dilapidated mill barn. The ornate fabrics covering their backs subtly suggest a circus setting, which is also hinted at in other paintings in the show, setting up an underlying contrast between the natural and the artificial, and by implication between the real and the otherworldly.

In a departure from her earlier works, which frequently were made with oil paint on board, Andersson recently began using oil bars and acrylics on canvas. Part of a self-conscious effort to capture an experience rather than a specific event, the compositions are freer and more abstract. This is particularly evident in Holiday (2020), where seven riders on horseback almost blend into the flattened, intricate background, which is hardly recognizable as a landscape except for the gray, distant mountains along the horizon. Acknowledging that her works are not simply inspired by poetry, but about poetry, Andersson has further noted, “Everything boils down to a memory, the perception of a memory, and how to displace a memory.”