Mo Kong

“Making A Stationary Rain On The North Pacific Ocean”

New York, 137 West 25th Street

Blurring fact and fiction, art and science, truth and near-truth, the artist turns the gallery into an immersive installation exploring a not-so-distant future in which China and the United States are in the midst of a political Cold War, echoed externally by an atmospheric antagonism rendered by climate change that has turned China and the U.S. into the hot and cold centers of the world.

Seeking The Common Ground (detail) 2019 Mini freezer, handmade popsicles with newspaper confetti, dish racks, preserved tropical fruit, frozen cube fruit, plant lights 18 x 19 x 27 inches

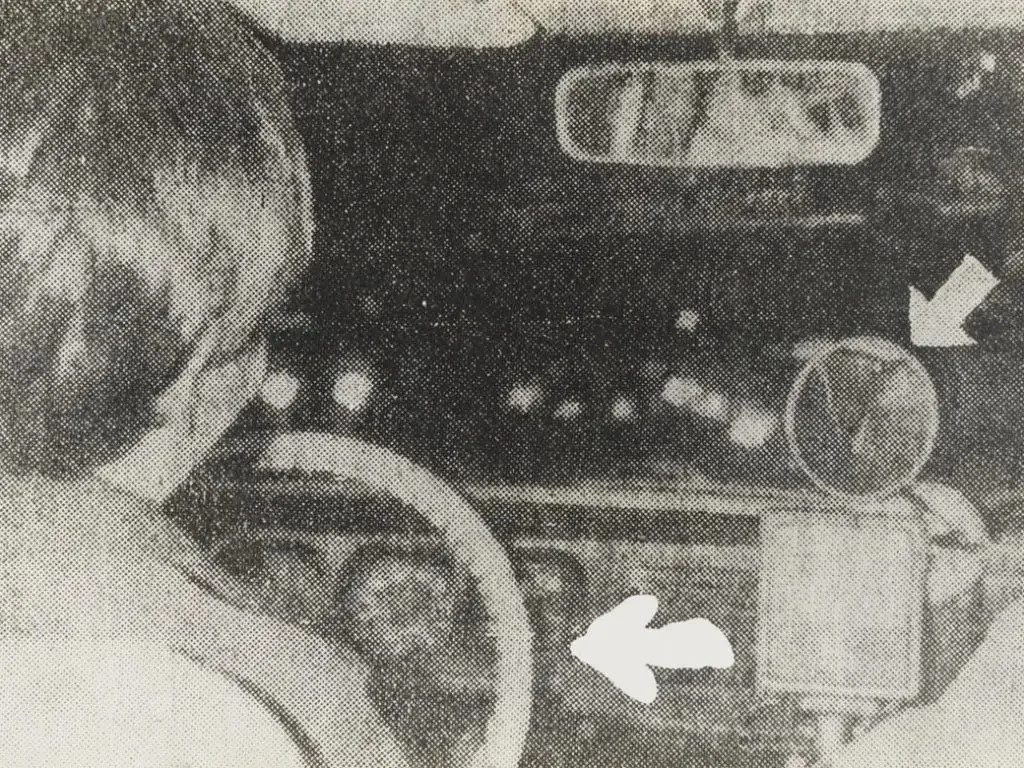

Kong’s visual exploration of his own scientific and journalistic research uses climate change as a lens into contemporary geopolitics, neo-nationalism, human migration, human rights, and censorship, among other topics. Central to and grounding the exhibition, Kong has carefully gridded out the gallery with blue painter’s tape, delineating the latitudes and longitudes of the worlds within the installation. The grid marks coordinates, not countries; this is a type of mark-making that allows us to locate ourselves beyond national and temporal boundaries, but also allows our movement and migration to be tracked in turn via GPS. Placed throughout the gridded gallery, a rectangular glass vitrine sits on the floor filled with foam, salt, coal, and other materials, recalling the contents of the North Pacific Ocean; tubes of honey line the walls, referencing the practice of honey smuggling, trade wars, and human migration; sand, blown glass, and preserved fruit skins enclosed in a bent lead frame recall evaporated lakes; vertical poles representing weather stations symbolically observe and measure fictional climates; and scent diffusers pipe in natural oils associated with either country.

Making A Stationary Rain On The North Pacific Ocean (Fungus) 2017 Fungus, bug light, digital prints 15 x 20 inches

Referencing Kong’s own experience as a recent Chinese immigrant to the United States, his past occupation as an investigative reporter, and the necessity of the self-censorship he learned to employ as an information strategy while making political art in China, the artist cloaks facts in fantasy in order to explore complex systems of thought surrounding environmental crises and sociopolitical issues. In her exhibition catalogue essay, Danni Shen writes that “Self-censoring has led to the artist’s process of filtering information–clues and hidden evidence–in such a way that viewers are able to draw connections between disparate points of reference. Under the camouflage of scientific research, the work’s political subject comes in and out of focus.” In Kong’s world, knowledge is not linear, information is not neutral, and truth does not require fact. But in order to evade or bypass a system or grid, one must learn to navigate it; and in order to arrive at or depart from a place, one must first learn where it ends and begins. The answers are not always as obvious as they appear.