Carlos Motta

“Conatus”

New York, 535 West 22nd Street

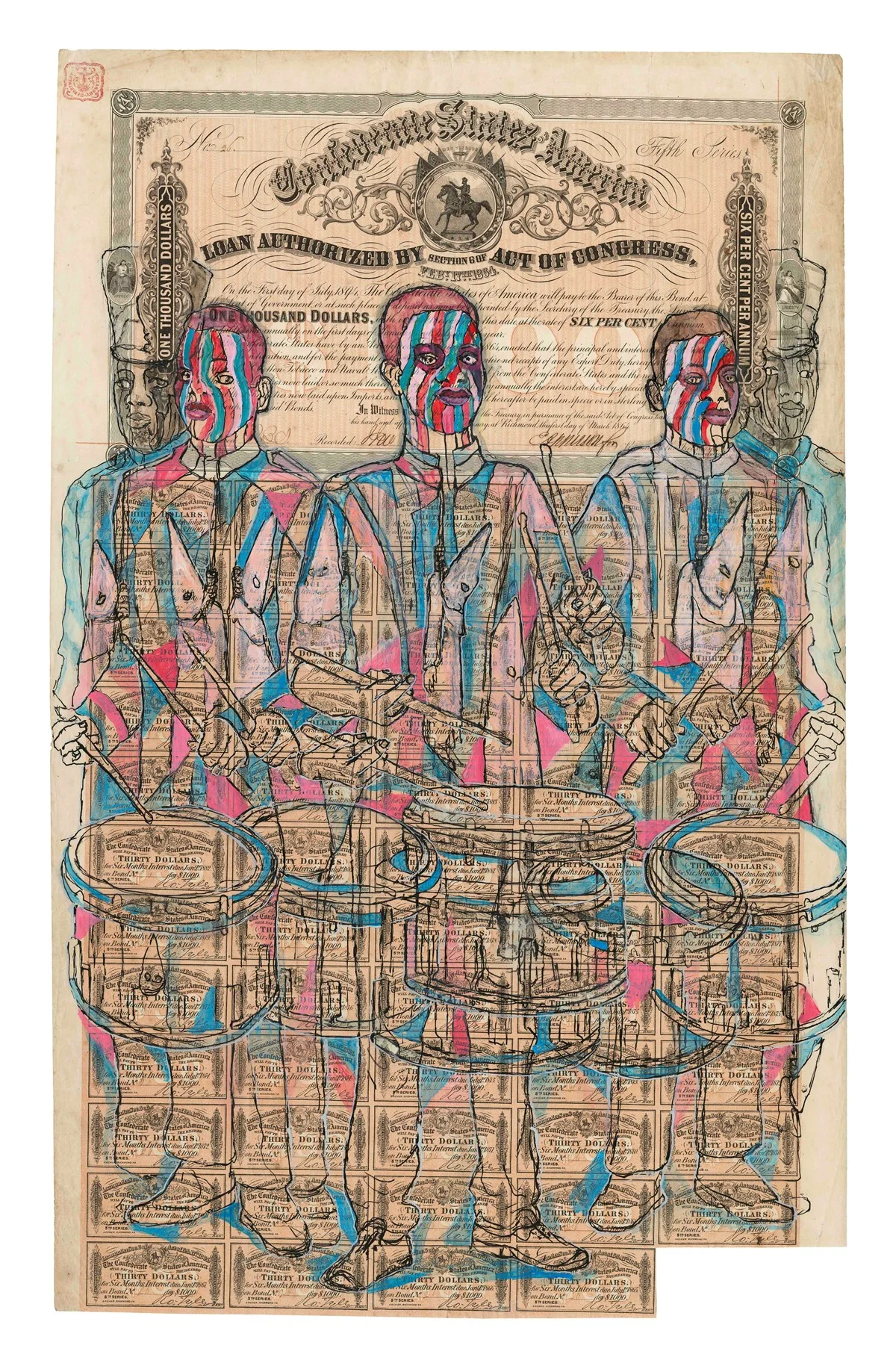

Comprising new work in several media, the exhibition is grouped in three sections: a trio of related videos, a series of photographs, and a cycle of framed objects that traffic in appropriation and assemblage. Latin for ‘striving, endeavor, inclination,’ ‘conatus’ means the desire of each person or thing to persist in itself. In Motta’s new work, subjects persist and even thrive amid the legacy of historical trauma.

Motta’s multilayered 24-minute video Corpo Fechado: The Devil’s Work (2018) screens in the first room. It relates the true story of Francisco José Pereira, an 18th century man who was kidnapped from West Africa and sold into slavery in Brazil. As a means of survival, Pereira along with others in enslaved communities developed syncretic spiritual practices that mixed African with Christian tradition, notably in the form of bolsas de mandinga — amulets to protect fellow enslaved persons from injury. In 1731, after Pereira was sold to a slave holder in Portugal, the Lisbon Inquisition tried him for sorcery. He was also charged with sodomy, since he confessed to copulating with male demons in the course of making the amulets. He was exiled from Lisbon, condemned to end his days enslaved in a galley. Corpo Fechado imagines Pereira as the agent of his own narrative, reclaiming the terms of representation from the account of his own destruction.

The video interweaves Pereira’s story, drawn from court documents, with two other texts. The first is Letter 31 – The Book of Gomorrah, an 11th century screed by the Italian monk Peter Damian (now a saint), which laid significant foundations for Christianity’s millennium of persecuting so-called sodomites. The discourse of the sodomite also played a central role in European colonialism, a theme Motta has extensively explored in earlier video works like Nefandus Trilogy (2013) and the installation Towards a Homoerotic Historiography (2014), currently on view in the exhibition Home is a Foreign Place at The MET Breuer. Damian stalks the film as a robed and faceless menace, in one scene playing chess with a Portuguese conquistador. The second intertext is Walter Benjamin’s famed Theses on the Philosophy of History (1940). In Corpo Fechado, Pereira incarnates Benjamin’s Angel of History, a seraph caught in a storm blowing from Paradise, propelled inexorably into the future yet facing backward, doomed to see only the wreckage of the past. To paraphrase Benjamin, Corpo Fechado grasps the constellation our present era forms with definite earlier ones. It uncovers messianic struggle from the shadows of history.