Hilton Als on Alice Neel

"Alice Neel, Uptown"

New York, 525 & 533 West 19th Street

Artspeak director Osman Can Yerebakan met the influential art and theatre critic Hilton Als at David Zwirner to talk about his curatorial project Alice Neel, Uptown, a personal and meticulous exhibition focusing on paintings Alice Neel created throughout her five-decade-long residence in New York’s East Harlem and Upper West Side. Accompanied by an illustrious publication featuring texts by Als and Jeremy Lewison, the exhibition chronicles an artist’s personal and creative journey over the decades, while chronicling complex social and political narratives embedded in American history.

— There exists a political determinedness and resilience in sitting as a political stand. Opposed to taking the streets for self-expression, being simply present in a certain time and space conveys a silent, yet sharp activist tone. What does sitting mean for you in terms of Neel’s work? Do you believe there is political gesture in stillness of her paintings?

There is a chapter in the exhibition catalog where I talk about Pregnant Maria painting. I talk about how women are always waiting; they have to measure every act very carefully. In Michel Auder’s wonderful documentary about Alice, when asked how she feels about being discovered at later age, she says, “it was okay, because I had the paintings.” There is something to be said for the hierarchy of talent and the ability to wait a trend out. While Alice was making her paintings, all male-dominated movements came one after another: Abstract Expressionism, later Minimalism, and then Pop Art. When women finally started to have a voice, they were still marginalizing Alice, because she was painting other people, not herself. The important element here is to wait out a trend and to become a winner in the end.

Alice Neel, Pregnant Maria, 1964 Oil on canvas Private Collection. © The Estate of Alice Neel. Courtesy David Zwirner, New York/London and Victoria Miro, London.

— As a white artist, Neel was invested in discussion of unjust policies and racial discrimination before these issues entered so-called mainstream representation in art. How do her paintings and their socio-political volume translate to our times in this sense?

On that very issue, I’d like to quote Alice from an interview she did in 1992 with Barbaralee Diamonstein:

What amazes me is that all the women critics respect you if you paint your own pussy. They didn’t have any respect for being able to see politically and appraise the Third World. Nobody mentions that I manage to even see beyond my own pussy politically. But, I thought this is a good thing. If they had a little more brains, they should have given me credit for being able to see not the feminine world, but my own world.

I think her saying indirectly some way that she identified with people she was painting is brilliant. Women’s issues, in a way, are Third World issues, because they belong to the Third World, they are not first class citizens. She lived in this milieu that reflected who she was, physically and culturally. Her tone was never condescending, or you never get a feeling that she felt different from her models. What she finds is a beautiful way of communicating. One of the reasons I responded to her work at an early age was because I didn’t feel she was talking down to me. I felt that she was someone almost reaching out to touch me.

— It seems that Neel has had tremendous impact on your work as a writer and curator. This was evident during your introduction of this exhibition at David Zwirner’s press event in January. Could you talk about your association with Neel’s work that exceeds the traditional a dialogue between artist and curator?

I think Alice and Diane Arbus are the greatest portraitists of the 20th century. One of the reasons I love them as artists is because they were very honest about what they were depicting with some aspects of themselves and some aspects of their feelings about themselves. I think Post-War American was really about ultimately finding metaphors in disguise in the most part and I loved that, in a way, it was unfashionable to be a portraitist at the time. Alice did not get much attention until she was much older and Arbus received very sporadic acclaim throughout her life. There is something very moving about people who keep pursuing what is not fashionable. They simultaneously expose people to their work and to their most personal aspects. They find real life metaphors for what they really are.

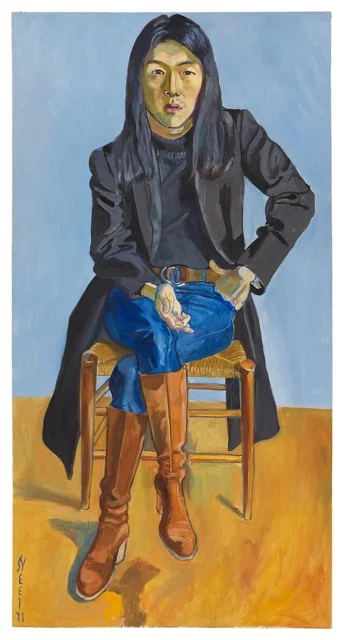

Alice Neel, Ron Kajiwara, © The Estate of Alice Neel. Courtesy David Zwirner, New York/London, Victoria Miro, London, and Xavier Hufkens, Brussels.

— You support works in this exhibition with accompanying text in the catalog, while you add depth and context in Neel’s subjects. How do you consider the relationship between art and literature, or to be more precise, between figurative painting and prose?

I thought it’d be nicer for the reader not to have one big chunk of writing and be able to individually correspond to paintings. When people look at images on a catalog, they usually flip through the pages to find an image mentioned in an essay. Why not reorder that and make it about the paintings, I thought. I tend to define the paintings through paintings, and I don’t try to make great critical arguments as they are already embedded in the works. In prose, the energy of the writing comes from the author’s feeling that they will communicate through their words, and similarly, portraitists tend to connect directly with the audience, as well.

— New York has immensely changed since Neel painted her friends and family in East Harlem. Uptown and other parts around five boroughs have faced crucial transformation as result of gentrification. In your opinion, what would be Neel’s perception of New York today?

Weirdly, the building Alice lived is still the same (laughs). There has been gentrification around it, but the block stayed quite the same. When we talk about change in society, we talk about access, and how much people of color are given access. The scope of what has happened in that neighborhood is that it is no longer a neighborhood. Then, your kids would be my kinds; however, now, the street life is not prevalent. They are not connected as neighbors any more at personal level. One important element of Alice’s work is that she knew all these people she painted; they were her world.

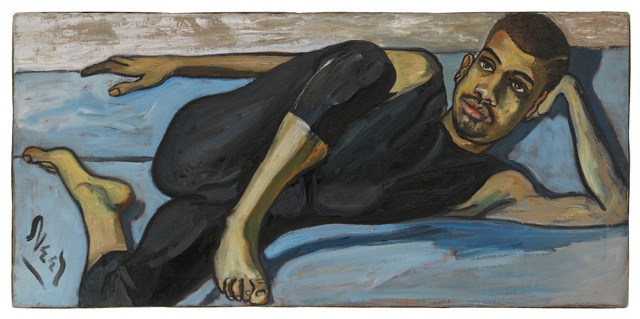

Alice Neel, Ballet Dancer, 1950 Oil on canvas Hall Collection. © The Estate of Alice Neel. Courtesy David Zwirner, New York/London and Victoria Miro, London.

— I’d like to particularly talk about Ballet Dancer in which a young African-American man, donning what possibly looks like a tight black leotard, reclines on a blue coach, while his right leg crosses over the left. Unlike other posers who mostly sit in stoic manners, he conveys further exuberance and corporeality with that gesture. What is your opinion about this painting or any other particular work you find striking?

That painting is a great example of her interest in depicting queerness. She lets us assume… In the other room, there is the painting of Ron Kojiwara who died in 1991 due to complications from AIDS. I have really special affinity to that painting in particular, because what she was conveying is something about self-defensiveness of style. There is a great deal of androgyny that goes with his long hair and knee high boots. The same exists for the ballet dancer, too. His relaxation and the way he puts himself out there declares his presence. He is not working against her, but still making his own statement. She is doing that wonderful thing of upsetting people’s ideas about how men are supposed to sit or behave and how women should be the odalisque, but not men.

On view through April 22 , 2017

Cover photo: Alice Neel, Alice Childress, 1950 Oil on canvas Collection of Art Berliner. © The Estate of Alice Neel. Courtesy David Zwirner, New York/London and Victoria Miro, London.