Samuel Levi Jones

Burning all illusion

Galerie Lelong

New York 528 West 26th Street

In a world filled with fake news and media noise, Samuel Levi Jones creates room for quiet contemplation. Assembled from destroyed academic books, his works on canvas highlight those who control the content of, and are chosen for inclusion in, texts considered to be “all-encompassing” and “universal” by the West. Equally invested in the exclusions made by these encyclopedic and academic volumes, Jones recently created a new series of work made from texts on black history, law, music, and education. He brings to light those missing in widespread (and often whitewashed) institutional source materials, which reflect broader power structures in society.

A few days after the U.S. presidential election results were announced, contributor Shama Rahman spoke with Jones about Burning all illusion, the artist’s first solo exhibition with Galerie Lelong in New York City. They discussed unexpected elements of his newest works, behind-the-scenes stories of his material acquisition process, and current events.

(This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.)

How did you choose the materials and particular texts for the works in Burning all illusion?

Earlier this year, someone I know from the African American Studies Department at UC Berkeley told me the department was getting rid of some books and asked if I wanted to use them. The books included African American encyclopedias and texts on a variety of subjects, such as black music and history. I had never thought of using or destroying that material, but I came to see it as a way of rewriting what I had worked with before.

Acquiring the materials is an experience of its own that goes with the storytelling of the works. Last August, I got materials from a woman who was living with her daughter and grandkids, one of whom had a medical condition that required 24-hour care. She spoke about fighting the court system and medical system to get health care for her grandchild, and how difficult it was to get empathy from the white judges who made decisions. Sometimes the stories are heavy, but it’s all a part of the process.

How was the process for these new works different from methods you have used in the past?

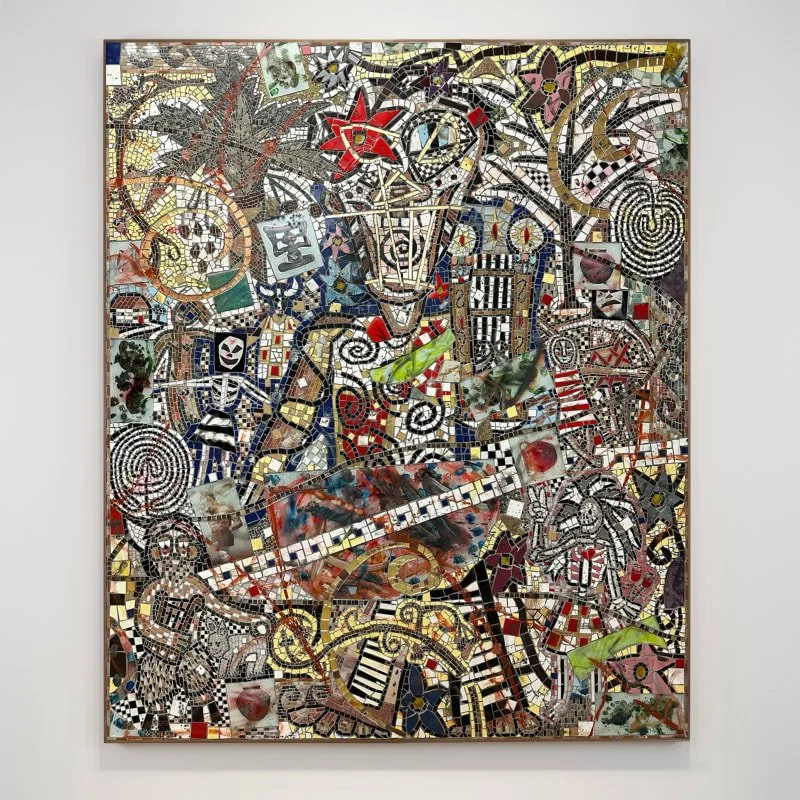

When I started, I made one painting from a single set of encyclopedias, and that evolved when I began working with law books because there are many, many of those books—several hundred that can’t be used at once. There is more of a mixture in the new works. Some of the pieces aren’t monochromatic. They’re more abstract and the colors are mixed up. They are different shapes and sizes, and include a little bit of layering.

It’s been twelve months since I’ve been offered the source material I used in this show and I was waiting for an opportunity to really offer something new and different. I’ve just been able to spend a little bit of time with it, digest it, and work with it. It’s still in the grid format, but it’s just a little bit broken as well.

Selective Proof of Facts detail

Tell me about the titles of your works and the stories they share.

A huge part of my process is how I title the works. I title my works after events that have happened as a way of sharing stories and having conversations.

Some of these works were made from Ohio law books I picked up and I made one piece titled after a young woman who was murdered by a police precinct. That got me thinking of Ohio and women killed by police brutality, and I found a list of fifteen women who had been killed that way. It seems like popular media, for the most part, gives attention mostly to black men brutalized by police officers, when in fact, there are a lot of different cases of women and white people too. I’m thinking of the people who don’t get attention and making a connection with those individuals by linking them to the titles and creating consciousness around their stories.

What do you think the relationship is between your use of historical material and the mainstream news cycle?

Working with books is not about the text and the information itself, but about thinking deeper and how we fail to dig deeper. When a murder happens at the hand of a police officer, a police officer will think that in and of itself is a problem, but we are really addressing a systematic problem that is very deep and layered. With the encyclopedias, I’m thinking about who controls the information and what they decide to leave in or leave out. I look at the encyclopedias as a stand in for the power structures we don’t visibly see, tearing that apart and destroying it, then putting it back together to create something visual in order to have a dialogue about power structures in different fields, like education, law enforcement, and the government. I’m really trying to break those structures up and getting people to think differently. The object isn’t the end.

Do you think this year’s election results will change things, especially the stories you come across in your process?

I feel like there are a number of people who have been uncomfortable and unhappy with the things I’ve talked about, and now we are in a situation where so many more people feel uncomfortable and affected. It could be a spark that enables people to be more engaged. If people don’t see they are affected, they aren’t worried about things, and carry on as if there isn’t a system that needs to be restructured or changed. We feel comfortable and let things distract us. Now, the comfortable people feel uncomfortable. Hopefully what happened will lead people to be reactionary.