Jennifer Rubell

Housewife

Sargent’s Daughters

New York, 179 East Broadway

Our editor Osman Can Yerebakan interviewed Jennifer Rubell about her first New York solo exhibition. Housewife, on view at Sargent’s Daughters in Lower East Side, includes a series of participatory sculptures that invites the audience to engage in performances that reenact house work, while questioning the presumptions about female identity and womanhood in society.

— You began questioning domestic activities and women’s status in society through your food art performances. How did the transition towards this exhibition take place?

Jennifer Rubell: I see everything I do as the same thing. A performance is a painting is a sculpture is a film. What they all have in common is an exploration of the relationship between the viewer and the object. The acknowledgment of the viewer as a participant in the work could be characterized as a feminine gesture: paying attention to the other, care taking… This naturally leads to questions about domesticity, femininity, and feminism. The form of the work and its subject are mirrors of each other.

— Similar to how third wave feminists owned many derogatory terms that were used to define women, you claim certain so-called womanly roles in this exhibition. Moreover, you ask your audience to practice in these activities. Do you find odd similarities between performance art and house work?

J.B.: It strikes me that what artists consider painful, extreme, durational work bears a close resemblance to what many blue collar workers—men and women—do every single day without any recognition whatsoever. Performance art as I practice it, which is to say performance that involves the participation of the viewer, engages with what you might call women’s work. The viewer’s role, though, is fluid. They are at times the housewife, at times the husband, at timeS the courtier, at times the courted.

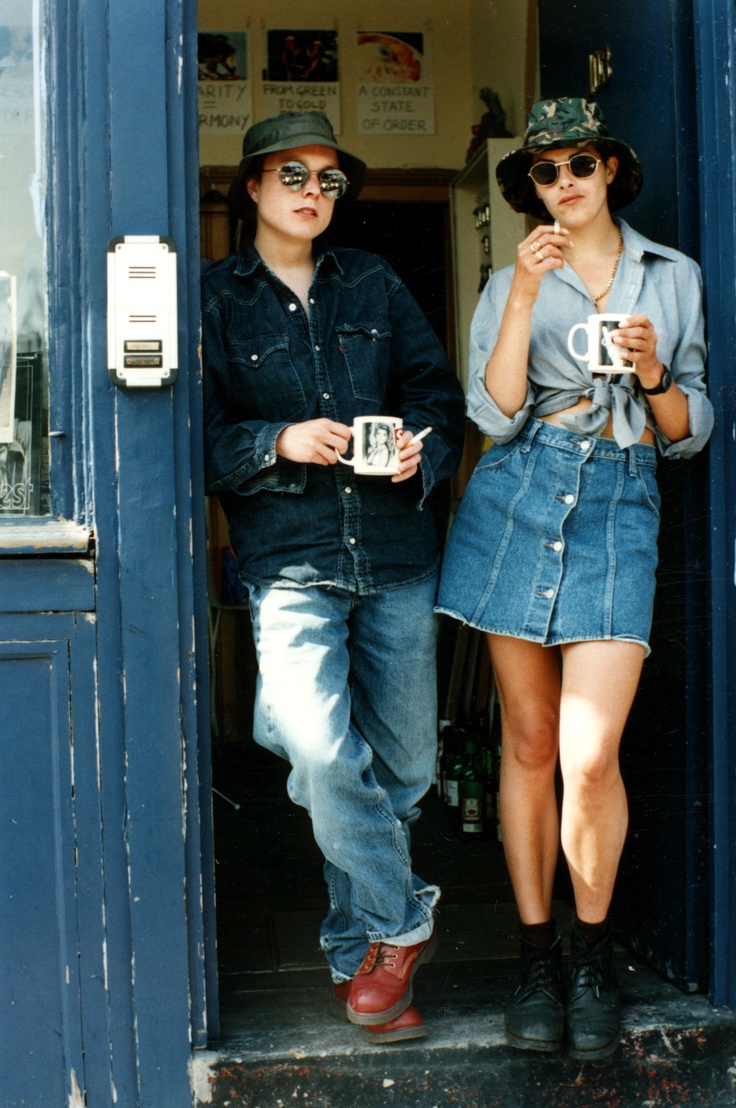

Installation View from Jennifer Rubell's Housewife at Sargent's Daughters

— By activating their roles as participants, you invest in an expansive dialogue with your audience. Such conversation has been a crucial thread in your work. What kind of mutual understanding and trust do you expect from your audience?

J.B.: I don’t have expectations of my audience. I think it’s fair for them to have expectations of me. My work needs to offer a clear prompt to interaction. Here is a pair of shoes on a pedestal. Here is a staircase that leads to the top of that pedestal so you can stand in the shoes and hold the vacuum cleaner. The prompt is not in words; it is built into the visual language of the piece.

— The artworks in this exhibition all date 2017. How did the election results affect your work?

J.B.: Trump and Clinton’s campaigns were the background noise of the making of Housewife. Every work was nearly complete by the time the election actually happened. The only piece that has any direct relationship to the election is Vessel, the life-sized cookie jar of Hillary’s pantsuit. I tried to make it as accurate and humanist a portrait of Hillary Rodham Clinton as I could. I knew that would make it interesting whichever way the election went. If it was truthful enough, her destiny would be built into the piece. And in the end, it was, the piece has her stepping off a pedestal, for instance.

— You celebrate Hillary Clinton as the perfect rebel against the traditional assumption that women cannot build careers and families at the same time. Do you find connections between being a politician and a mother?

J.B.: I’m not sure if the piece celebrates Hillary Clinton or not. It zooms in on the seeming contradictions within her that I feel within myself. I don’t know if they’re actually contradictions, or just two versions of the same thing. To make the piece, I myself acted as both the professional artist and the cookie-baker.

Rubell, Jennifer, Vessel, 2017 Resin, food-safe paint, oatmeal chocolate chip cookies (from Hillary Clinton's recipe) Courtesy of the Artist and Sargent's Daughters

— How does your family’s influence in the art world affect your artistic practice? Is there a relationship between art patronage and creating intangible artworks?

J.B.: I’ve always been around a lot of great art and a lot of great artists. Early on, I absolutely did not feel comfortable making durable objects that would compete with this work, and so every single thing I did was ephemeral. I started making durable objects accidentally. They were sculptural parts of performances, and then people started asking to collect them. Slowly they took on a life of their own, until they began to exist on their own terms, outside the realm of performance, inside the realm of galleries and museums. The objects and paintings create the same type of participatory experience as my performances, but permanently, immutably, and I have to say, that’s pretty exciting. Their permanence makes them more challenging. It pushes me to resolve things, formally, experientially, conceptually, that can be more open-ended in a performance. Resolving an amorphous idea, emotion, state-of-being into an object is a profoundly satisfying activity.

On view through February 26, 2017