Joyce Kozloff

"Girlhood"

DC Moore Gallery

New York, 535 West 22nd Street, 2nd Floor

We meet on a bright Saturday morning at the gallery in Chelsea. Kozloff is smiling and filled with energy, dressed in all black with a touch of color at her red suede sneakers. She gives me a tour of the show, including the smaller collages and drawings from her 2001–02 series Boys’ Art, which laid the foundation for her current work with maps and pre-adolescent drawings. After the tour we sit down to chat about maps, feminism, and Kozloff’s artistic career.

Y.V: As a pioneer of the Pattern and Decoration movement in America in the 1970’s, how and when did your interest in Pattern and Decoration start?

J.K: It started with feminism. Not for all of us, and certainly not for the men in the group. I was always nervous as an art student when they would call my paintings decorative, because that was really bad. Then, in the early 70’s, I became involved in the Women’s Movement. I started having conversations with other artists about breaking down hierarchies and stereotypes. I realized that the word decorative was about the decorative arts, which are largely anonymous and often done by women and people from other cultures.

For me, I got over my fear and I wanted to claim it, and I wanted to make the most decorative work I could possibly make. Through a process of osmosis I met other artists who were also thumbing their noses at formalist and minimalist art, which was so dominant in the art world at that time. We were looking for a way out and we were young, so we just went as far from that as we possibly could. I loved the global world of the decorative arts that was opening up to me; it wasn’t a part of my formal art education, which was Western painting and sculpture. I travelled, went to decorative arts museums, read books. It was very exciting for me.

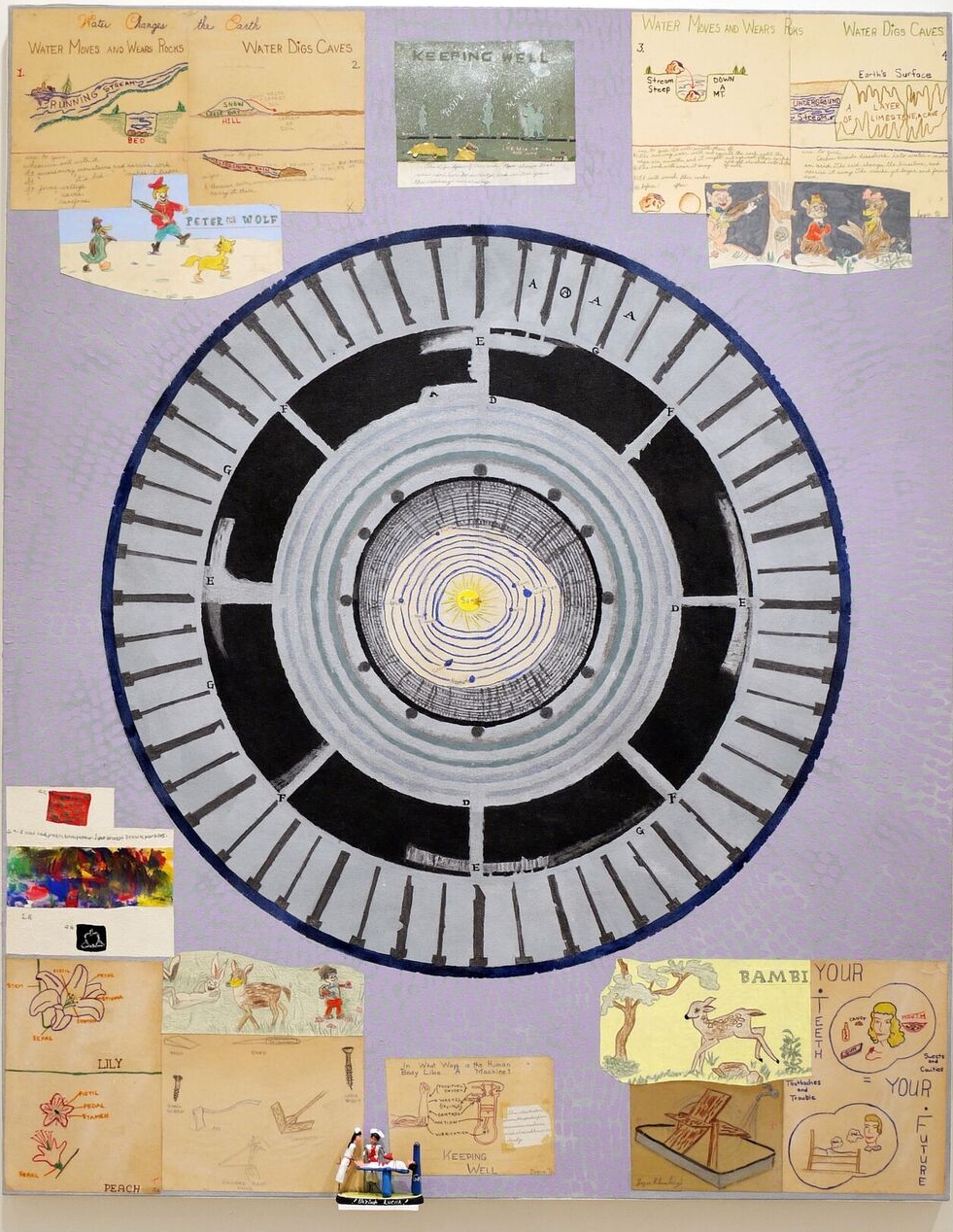

Science and Sentimentality, Courtesy of the artist and DC Moore Gallery, New York

Y.V: What do you think about the current use of the word decorative?

J.K: I still hear people—particularly in the schools—use it as a pejorative. It has been so absorbed into current art practice that if you go around to galleries there’s a lot decorative work all the time. I don’t think younger practitioners necessarily remember the group I was a part of, but they are inspired by some of the same sources we were inspired by, independently. Maybe then they find out about us and research us. Now with the Internet and globalism, everything is available to everybody. In other parts of the world, artists are also appropriating—and I still appropriate.

Y.V: Artists have many reasons for using maps: psychological, political, even illustrative and narrative. What was one of the main reasons for you to use maps in your works?

J.K: For about twenty years, in the 80’s and 90’s, I was primarily doing public art. I created16 public art projects, and I had little time for my private work because these projects were very hands-on. When you start a project you are given floor plans, elevations, diagrams. Then I would have a model made and begin to imagine it. It was a structure that I could work into, build on, elaborateand decorate. At some point I realized that [the floor plans] were similar to maps, so I started thinking about cartography as a structure for my private work. I’ve been mapping ever since.

I keep thinking it’s time to move on to something else, but there are so many different kinds of maps that I have used in different ways. The maps are embedded with all kinds information—about cultures and politics, the way the borders change. Who makes the maps? Is the colonizer making the map of a conquered territory, changing the names and planting its own flags? I am endlessly drawn to these things. For me it is not the end but the starting point.

Y.V: You embedded your old drawings and artifacts from your childhood into your recent map works. Is it a way for you to keep that childish innocence in your works?

J.K: I didn’t know the drawings were there. I have a very poor memory from my childhood. My brother, who is five years younger than me, remembers things that I don’t recall. After finding these drawings, I didn’t have a strong reaction to them. I would take them out, look at them, and put them away. A couple weeks later I would look at them again. But it did really amaze me that I had made so many maps as a child and I didn’t remember.

Then and Now, Courtesy of the artist and DC Moore Gallery, New York

Y.V : What about your Boys Art series from 2001-02 , how did you end up collaging your son’s drawings into your works?

J.K: I kept my son’s drawings that he made as a kid: I love them. When I found my childhood drawings in my parent’s house, I found my brother’s drawings too. I always remembered the battle drawings he used to make, little soldiers shooting off the ships. It amazed me. No one in the family knew where they were, and it wasn’t until two years ago that I found them. It was the memory of him making them as a little boy while I was doing these girly drawings that really interested me. Then as an adult, I saw my son making warring superheroes, the kinds of drawings that girls don’t make. I asked my husband, who is ten years older than me, if he had any drawings from WWII. He said he had made them obsessively but he doesn’t have any, and his family didn’t have them either. Most people don’t keep them. Then I asked my friends if their adolescent sons were currently making those drawings.

““It seems that today boys play war video games and there’s not so much drawing going on. All of this is kind of archaic; it is of another moment, and even the kinds of things I was drawing were pre-TV. I didn’t grow up with television, I grew up with these books. ””

Y.V: Most of your early works were inspired by Islamic motifs that you came across during your travels and through your research. What intrigued you the most about non-Western cultures?

J.K: There are two kinds of patterning: floral and geometric. At a certain moment in the 1970’s I was looking at different kinds of pattern, and I was drawn to Islamic pattern because it is geometric. I was coming out of geometric abstraction, moving away from it. Islamic geometrical patterning is the most complex and the most interesting. It is built on a system of overlapping grids, a vertical/horizontal grid and a diagonal grid.

In Western decorative arts, patterning usually is on one grid, a figure ground or a repeat, whereas Islamic grids can weave in and out, and become complex, like those star patterns that keep turning. I was interested in finding my way into them by not repeating the same colors, but changing them so that you could enter a dense maze, and leave it.

I expanded these to very large paintings. Towards the end of the 70’s I started moving away from P&D, but came back to it a few years ago. It seems like I am going back in time. A lot of artists when they reach my age want to tie it all together, but I wasn’t consciously doing that, it just happened.

Courtesy of the artist and DC Moore Gallery, New York

Y.V: You created around sixteen public artworks over the years in many different locations, but you returned to studio practice due to the challenges you had with censorship by the end of the 90’s.

J.K: In one project, there was a question about the imagery and I had to take a few tiles out, after a long, painful negotiation. Then I worked on a team project here in NY, which was political, complicated, and it didn’t materialize. It wasn’t just that I burnt out on public art, but I also had many private ideas that I never had time for. I extricated myself gradually from all my public commissions, which take years to accomplish. I went back to the studio, made paintings and started showing in galleries again.

Y.V: You have been an activist in the feminist art movement since 1970. How did the challenges you faced shape you and your practice to this day, where women still struggle?

J.K: Men in power, abusing their power still. It’s so horrible! You know what? Some men are embarrassed because not all of them behave that way. For me, the feminist process began with the Decorative Arts. Thirty years ago was an exciting moment for women; we had activist groups, shared ideas, visited each other’s studios. There were women exploring the body, sexuality, personal narratives. A lot of that work is now very famous, but it was underground at the time, not even shown in galleries. It was the early days of performance. Video and new media were used to explore different aspects of identity. My subgroup formed around cultural feminism and particularly in homage to what women traditionally created, which was not acknowledged or even called art. I don’t think today people remember that as much as the work about the body and sexuality. Decoration was a very big part of feminist art, almost an archeological dig, to discover what women had made and celebrate it. That was where I entered and maybe that’s where I’m leaving.

The exhibition runs through November 4, 2017